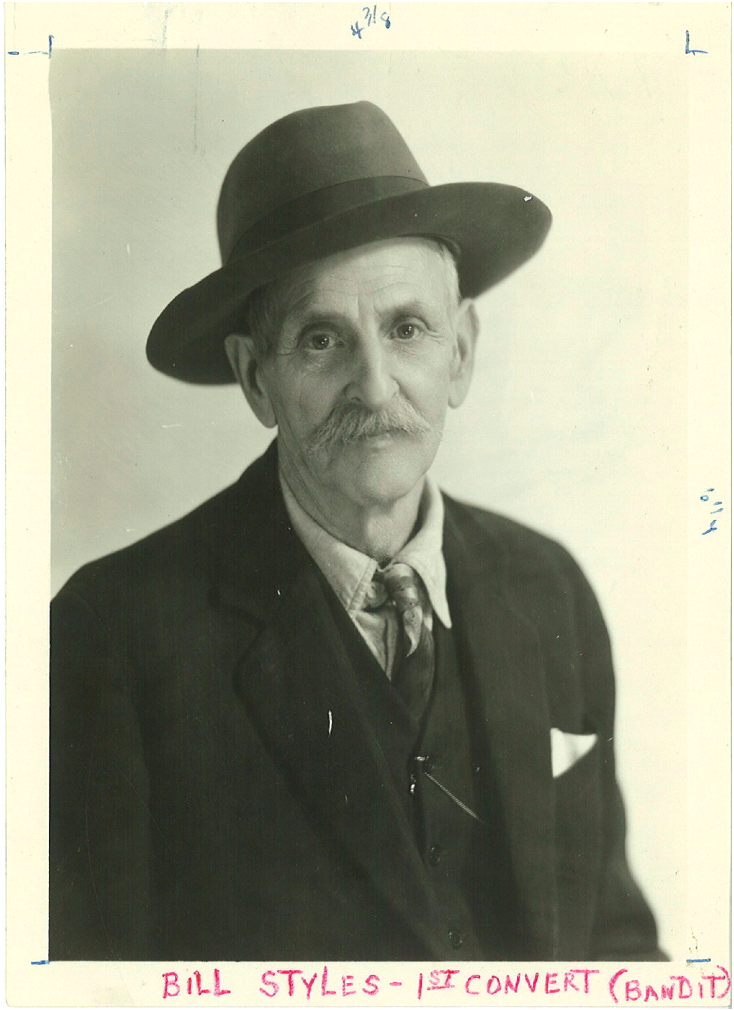

Introduction to Bill Stiles

Los Angeles in 1913 was fast becoming a modern metropolis. The streets were a crazy quilt of traffic comprised of pedestrians, horses, bicycles, and automobiles. It had grown from a small pueblo of fewer than 100 residents into a city of approximately 400,000 souls – many of them in need of saving.

The Union Rescue Mission had been leading people to God in the City of the Angels since 1891. One of the tarnished souls wandering the streets of Los Angeles on the evening of October 20, 1913 wasn’t a resident, he was a visitor to the city on a mission of his own – to rob a Southern Pacific Railroad train!

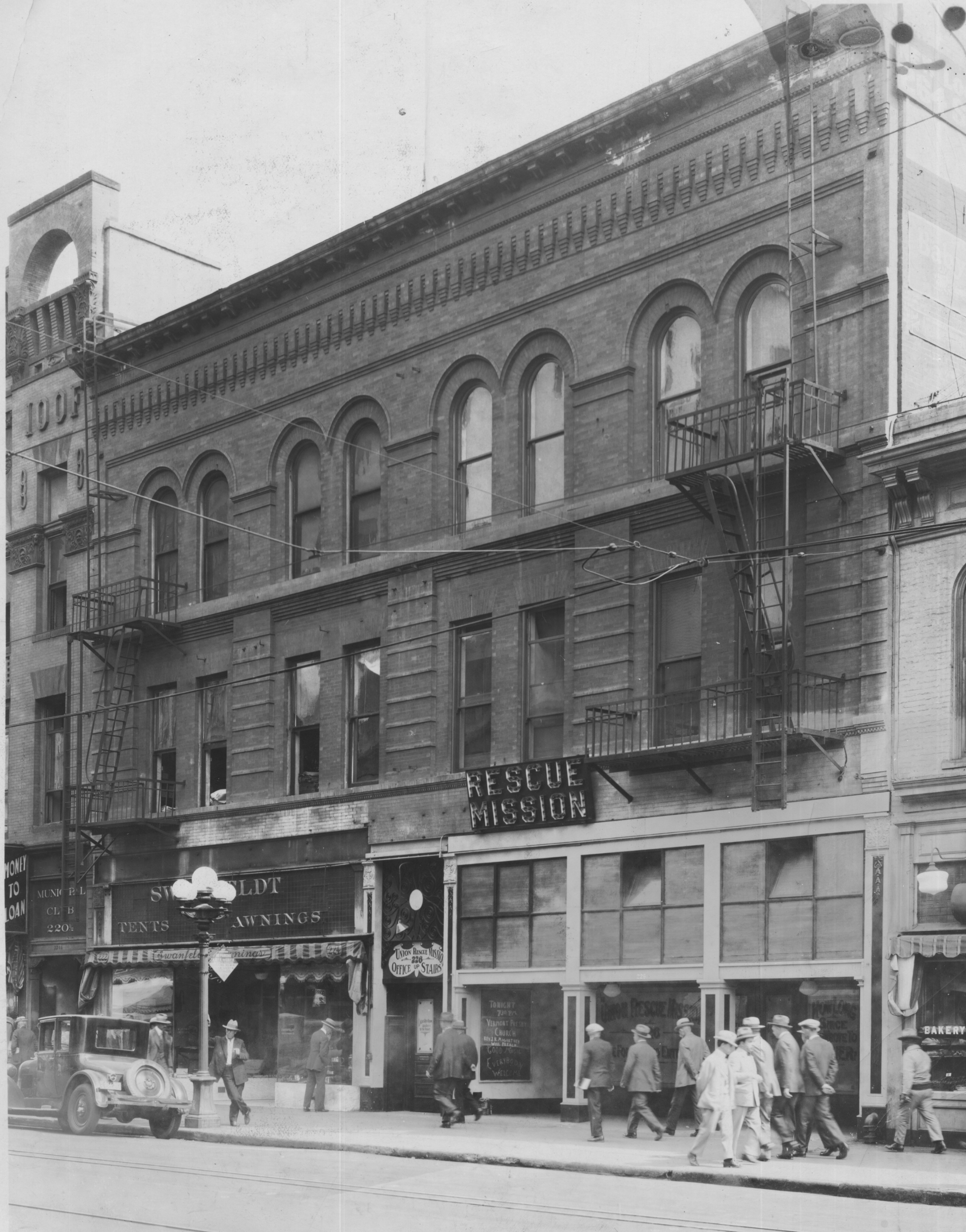

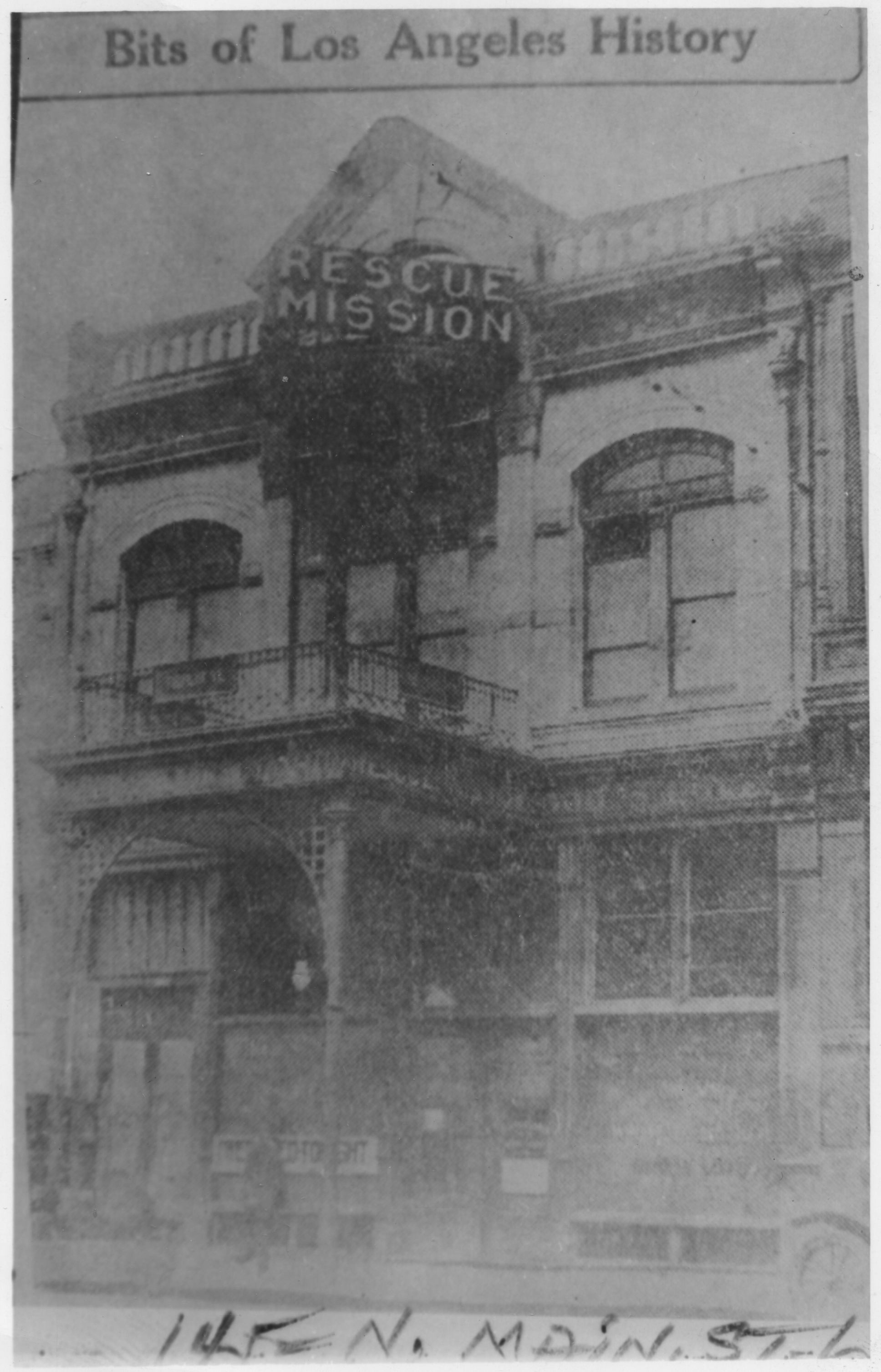

The man’s name was Bill Stiles, and he was in Los Angeles with two cronies making plans for a train robbery. When he’d left his downtown hotel to roam the streets of the city he had left all of the tools of his trade, guns, high explosives, and “soup” (nitroglycerin) in a suitcase in his room. As he was strolling along Main Street he spied a cop walking in his direction. Bill had been feeling uneasy about the upcoming robbery and seeing the cop did nothing to calm his nerves. He didn’t know if he was being shadowed by the law or if it was chance, but he wasn’t about to risk his freedom – particularly since he hadn’t been out of prison for very long. He had come upon the Union Rescue Mission at 145 North Main Street and figured it was as good a place as any to shake his possible pursuer.

Bill grabbed a seat near the front of the room, seeking anonymity in the crowd of worshippers. Stiles would describe the evening later saying: “I did not hear much of the service, for my mind was upon the work for the next day.” In fact his mind was so occupied with the next day’s work that he was just about to get up and head back to his hotel room when one of the Mission’s workers approached him and asked him to give himself up to God.

Stiles told the evangelist who had invited him into the fold that he didn’t believe in God because of the horrible life he’d lived so far. As he stood up to walk out of the Mission he realized that his legs wouldn’t move! He found himself fastened to the floor by, as he would later state, “a power not of this earth”. Bill may not have known it then, but he’d just been saved.

Despite an evening of tears, prayer and confession, Stiles returned to his hotel room that night. The next day he informed his co-conspirators that he’d found God and that he was finished with his life of crime. His friends told him that he was crazy and they went off to meet their own fates – both were gunned down in separate holdups.

It was barely dawn on the day after he’d cut his old life loose forever when Bill arrived at the Union Rescue Mission. The front door was locked, so Bill began tapping on a window until Mother Benton let him in. Mother Benton was surprised to have a visitor at such an early hour, but she was even more shocked when Stiles confessed to her that the suitcase he carried with him was filled with “soup”. With Stiles in agreement Mother Benton called the cops to surrender the explosives. When the officers arrived they asked a few questions then they carried off the suitcase, leaving Stiles uncharged.

Mother Benton was stunned by the contents of Bill’s suitcase, but if she’d known then that she was talking to a man who had been considered deceased for nearly 40 years she may have collapsed on the spot.

The man in Los Angeles who was calling himself Bill Stiles was at the center of a historical controversy that continues to this day. Bill Stiles was the name of one of the bandits who had been shot down during a raid conducted by the Jesse James- Cole Younger gang on a Northfield, Minnesota bank in 1876. And the man in Los Angeles was claiming to be the Bill Stiles that had ridden with the gang to Northfield!

The identity of the dead man in Minnesota has been the cause of controversy since the day of the robbery. So, too, has the actual number of bandits involved in the raid.

The reports contemporary to the time of the Northfield raid indicate that there were eight men involved in the crime. A poem entitled “The Robber Hunt” published in the Winona Republican in September 1876 refers to eight men:

“This is the eight, that smelled the bait,

That is, the malt, that lay in the vault,

That was in the bank at Northfield”

Was there a ninth man waiting outside of town? And if there was a ninth man, who was he? Could the man in Los Angeles be an imposter with nothing more than a good tale?

The speculation and controversy over the identity of the Los Angeles Bill Stiles (dead bandit, or live Christian convert) has continued unabated for 135 years everywhere but at the Union Rescue Mission. Once the Bill Stiles who presented himself at the Mission all those years ago found a faith in God, he found the acceptance of the Mission’s congregants who had no incentive to disbelieve him. In fact everyone at the mission felt that “a wonderful change had been worked in the heart of Bill Stiles”.

In the end perhaps it’s not important to know whether the Bill Stiles in Los Angeles actually rode with Jesse James and Cole Younger or not. A man who carried around a suitcase filled with guns and nitroglycerin would be considered an outlaw by anyone’s measure, and he would certainly be viewed as a man whose soul needed saving. Whatever had held Bill Stiles’ feet to the floor at the Union Rescue Mission on that October night in 1913 was true and good, for it was said of him that he was “our faithful night watchman, alert and watching while his fellows sleep, much as he used to, only for a different purpose”.

Bill Stiles passed away on August 16, 1939. As for the veracity of Bill’s story of his outlaw days – that’s between the old cowboy and his maker.

Note: If you’d like to learn more about Bill Stiles and the ninth man controversy, I suggest that you read The Jesse James Northfield Raid : Confessions of the Ninth Man by John Koblas.

Bill Stile’s Testament

It was on the evening of October 30, 1913, in the Union Rescue Mission, 145 North Main Street, Los Angeles, California that I was arrested by the Holy Ghost and gave my heart to God.

This was the first time I had been in a church service since a small boy, nearly 44 years before.

My criminal life began when I was 14 years of age back in New York as a pickpocket. I had Christian parents and a lovely home. My father was a practicing physician. They did all they could for me but the devil got hold of me in some way, and I seemingly could not keep from doing wrong. They sent me into the country, but I did no better there. I overheard them talking of sending me aboard the Schoolship St. Mary, and then I ran away.

I drifted westward, and in 1876 joined the James’ gang with the Younger Brothers, and was with them in the Northfield Robbery. I escaped the vengeance of the law, and made my way to Omaha, Neb. I had served three terms of one year each behind prison bars. In 1900 I was convicted of a crime and sentenced to life-imprisonment. When those doors closed upon me it was terrible; no one can know my feelings but those who have passed through such an experience. It was a life of torture; a living death.

On the 19th day of March, 1913, I got my release from prison, and friends took me to the state of Washington, where I found employment in a lumber town. I did not like it, however, and soon found a friend who gave me work for two months; but when he came to me one day and said that he could not employ me longer, I knew my past had been revealed, and became discouraged. At last I gave up trying to be good! I found it impossible, and determined to go back into my old life of crime. I knew it meant death to me, so I began to prepare for what I knew in the end would be the taking of life before they would get me. I was desperate, and once more the old outlaw spirit was upon me and I was becoming a demon at heart. I went to Tacoma and Seattle and looked up some of my old pals – men who did not care for their lives. With them I planned to go back into my old work of train robbing.

I came to Los Angeles on the 19th day of July, 1913, and began to look up this country, both along the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific railroads, preparatory to “striking” and then striking again. I went into the mountains for a month, in the vicinity of what is now known as Pisgah Grade, and drew my maps and laid my plans. I came back into the city and put my men (as they had bad records and were wanted by the police) in hiding. The night before the intended robbery I walked down Main Street, thinking over my plans and the course mapped out, when I found myself in front of a mission. Just then I saw a policeman coming down the street and naturally feeling suspicious, I stepped inside to avoid him and walked way up front.

I did not hear much of the service, for my mind was upon the work for the next day. I felt a little uneasy, for I had left my suitcase in my room, and in it some of the “soup” (nitroglycerine), some high explosives, and my guns. I had everything ready and so far my plans had gone smoothly; but as I say, I felt worried, and was just getting up to leave when one of the workers came to me and asked me to give myself up to God. The life I had lived did not allow me to believe in a God. I do not remember his reply, for when I attempted to get up I had no control over my legs. I do not know what you think, but I know my legs were fastened to that floor by a power not of this earth. I kept trying to get up, when a woman came and sat down beside me, and urged me to go up to the altar. I listened to her pleadings for a time and then consented to go, thinking it would do me no harm anyway. What seemed so strange to me was that I did not have any power to resist. It was not the woman, for I had been a woman-hater since my early life; it was the power of God. As soon as I gave my consent my legs were released, and I went up and knelt at the altar. I heard them praying, and a strange feeling came over me. It seemed as though something in my heart was loosening up, and I began to feel happy; then a warm light came from above and made my whole body burn. How sorry I began to feel for my past life of crime! I could not keep back the tears – tears of real repentance. I heard them tell me to repeat a prayer, but I had found the Lord before that. Oh, what a joy came into my heart!

I went out of the mission knowing that first real joy and happiness in the Lord, for I was conscious that my sins were forgiven. I could not go to bed for joy, but walked the streets for hours. I forgot all about the train robbery I had planned for the next day; forgot the suitcase and guns. Next morning after my conversion, I told my companions what I had done and they said I was nutty. I told them if I was, I hoped God would give me more. I then separated from my old pals and they went their way. I am sorry to say that two of them have paid the death penalty already – one was killed in a raid in the north, and the other in Arizona. For a number of days I sat in the mission. I was happy – happy for the first time in my life. Finally I began to come to myself and to think about the law, knowing that I was liable to be arrested, for I had revealed my past life. I thought about going away, but was held from doing so by a feeling of love that seemed to draw me closer and closer: and such a delight was in my heart and soul that I knew I was in the presence of God’s Spirit. I was experiencing the greatest joy I had ever known, and the peace of God flooded my soul. I kept getting happier and happier until it seemed as though I loved everybody and everybody loved me. I knew no evil, nor thought no evil – I was “A new creature in Christ Jesus.”

That heart of mine was as hard as stone; nothing had ever melted it, and my soul was black with many a crime, but the Lord took me and washed me as white as wool. There is nothing but the power of God that can take the wickedness of life out, and keep it out. During all my life I had walked in the valleys and through dark paths, until up from the depths below He lifted me out – of darkness into His marvelous light. I know that a man who has lived the life that I have can never reform, but through the power of God he can be transformed and given a new nature; it’s the birth of a new spirit. I would not take the whole world for the joy the Lord gives me.

I broke my mother’s heart, and sent her to her grave in disgrace. A dear old father and sisters and brothers have all passed away, and their last thoughts were of me. I think I can see them now, their faces shining with the glory of God as they look down upon me from the glory-world beyond the skies, and rejoice, for “He that was dead is alive again, and he that was lost is found.” Now in place of carrying guns to destroy life, I carry the Word of God that gives life – eternal life.

There is no such thing as reformation for one like me. It takes the power of the Blood of Jesus Christ to blot out transgression and clean one up. Nothing else can take away our sinful appetites and set us free from the power of the evil. He that is free in Christ Jesus is free indeed.

“Wherefore He is able to save them to the uttermost that come unto God by Him, seeing He ever liveth to make intercession for them.” (Heb. 7:25) The promise has been made and stands sure, but you can sit there until doomsday and it will profit you nothing until you come. Six hundred and forty-two times in His Word, God has invited men to come. “Whosoever will may come.” The “whosoever” covers every man, but the “will” may leave some of you out. “Whosoever will may come.”

I have had repeated offers to go back into the old life since my conversion. Men have even offered to supply the money for necessary outfit or equipment. But it was the strength that I got from God alone that helped me to stand.

[Signed] XXXXX

Note: After twenty-four years of a victorious life Bill Stiles recently passed to his eternal reward. His friends who were present the night he was saved and knew him intimately all during his Christian life, witness to the fact that he served his Heavenly Father faithfully to the end. – Ed.

March, 1937

Tongues were wagging on every floor of the

Tongues were wagging on every floor of the

“

“