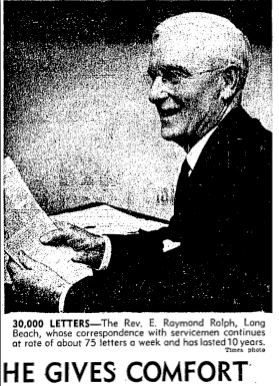

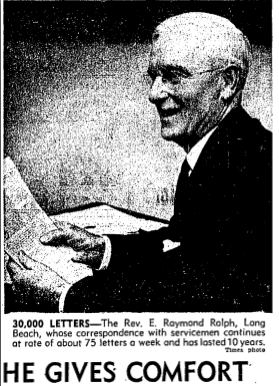

No mother ever wants to open the door to find men waiting to tell her that her child has died. For Mrs. Darius G. Farrar, Sr. of Camden, Arkansas, the news came not long after Darius Jr.’s 18th birthday: he had been killed at Iwo Jima. It was three years later when they brought the body home, and plans were made to bury him at the National Cemetery in Fayetteville, that mama started wishing she had a picture of what her boy looked like when he went off to fight. He’d shipped out from Los Angeles, and had made a visit to crowded downtown Los Angeles where he’d had his portrait taken. But he had been in such a hurry, the studio had to send the prints on to him in Guam. And when a buddy mailed them home after Darius’ death, they were lost in the mail. Mrs. Farrar was resourceful. She wrote to Reverend E. Raymond Rolph of Long Beach and asked his help in finding the negative—from among all the dozens of photo studios in downtown Los Angeles, with their tens of thousands of photos of Marines.  Pastor Rolph, a Baptist, was not chosen randomly. The servicemen of World War II and their families had no greater friend than this energetic soul, who was said to have sent more than 30,000 messages of encouragement or sympathy from 1942-52, officiated at more than a hundred military funerals, attended a thousand marriages (and performed a dozen), talked damaged men out of self-harm or harming others, welcomed a hundred babes named in his honor and somehow kept his thousands of pen pals straight through a convoluted filing system of his own devising. So when Mrs. Farrar asked for that figurative needle in SRO Land’s hay — “I have written to everyone I could think of. God knows how I have just wanted one good picture of Darius” — Pastor Rolph was not discouraged. He enlisted the aid of the Los Angeles Times, which gave the request a couple of column inches on page 11 of the April 2 edition, between stories warning of the dangers of socialized medicine and the tragedy of twin boys born by Caesarian to a dead mother in Illinois. And the photographic studio workers of Main and Broadway saw the story, and they went to their files. But not everyone has a filing system as precise, as well-kept, as Pastor Rolph. It was Winifred Thompson, manager of the Austin Studios at 707 South Broadway, who found the negative, in a brown envelope, in a box of trash. The kid was smiling fit to beat the band. She had prints struck, sent them on to Pastor Rolph, and he sealed them up with yet another letter to one more grieving mother. It was waiting for her when she came home from the burial. “From the depths of a true mother’s heart I want to thank you,” she wrote.

Pastor Rolph, a Baptist, was not chosen randomly. The servicemen of World War II and their families had no greater friend than this energetic soul, who was said to have sent more than 30,000 messages of encouragement or sympathy from 1942-52, officiated at more than a hundred military funerals, attended a thousand marriages (and performed a dozen), talked damaged men out of self-harm or harming others, welcomed a hundred babes named in his honor and somehow kept his thousands of pen pals straight through a convoluted filing system of his own devising. So when Mrs. Farrar asked for that figurative needle in SRO Land’s hay — “I have written to everyone I could think of. God knows how I have just wanted one good picture of Darius” — Pastor Rolph was not discouraged. He enlisted the aid of the Los Angeles Times, which gave the request a couple of column inches on page 11 of the April 2 edition, between stories warning of the dangers of socialized medicine and the tragedy of twin boys born by Caesarian to a dead mother in Illinois. And the photographic studio workers of Main and Broadway saw the story, and they went to their files. But not everyone has a filing system as precise, as well-kept, as Pastor Rolph. It was Winifred Thompson, manager of the Austin Studios at 707 South Broadway, who found the negative, in a brown envelope, in a box of trash. The kid was smiling fit to beat the band. She had prints struck, sent them on to Pastor Rolph, and he sealed them up with yet another letter to one more grieving mother. It was waiting for her when she came home from the burial. “From the depths of a true mother’s heart I want to thank you,” she wrote.

Ancient Beasts Below

During the digging of a well for a laundry on Winston near Main, at around 45 feet beneath the street, his workers hit something peculiar in a bed of gravel. On further inquiry, the substance was revealed to be portions of some enormous elephant-like creature, obviously buried long ago. The bones appeared to belong to a tusked creature of about twenty feet in length. Ribs were found, and an enormous ball joint. But as the bones crumbled to the touch, the workmen merely tossed them aside, and continued their labor.

While we can find no reports of a long-dead mammoth haunting the silent nighttime streets of SRO Land, we will be nonetheless peering closely in shadows for any hint of spectral trunks and haunches.

Hide In Plain Sight

If you were an eighteen year old boy from a small Northern California town and you’d just murdered five family members with a .38, what would your next move be? Raymond Latshaw found himself in that situation and he decided to run to a big city where it would be easier to live undetected. After abandoning his now deceased family in rural Auburn, he headed to the nearest city – Sacramento. Maybe he felt too close to home to be comfortable, but in any case he soon fled to San Francisco where he stayed at the York Hotel on Nob Hill. The York hotel would be featured in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 Film “Vertigo”. (In fact the hotel has been renamed the Hotel Vertigo!) I wonder if Hitchcock knew that a young multiple murderer had once lodged there.

If you were an eighteen year old boy from a small Northern California town and you’d just murdered five family members with a .38, what would your next move be? Raymond Latshaw found himself in that situation and he decided to run to a big city where it would be easier to live undetected. After abandoning his now deceased family in rural Auburn, he headed to the nearest city – Sacramento. Maybe he felt too close to home to be comfortable, but in any case he soon fled to San Francisco where he stayed at the York Hotel on Nob Hill. The York hotel would be featured in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 Film “Vertigo”. (In fact the hotel has been renamed the Hotel Vertigo!) I wonder if Hitchcock knew that a young multiple murderer had once lodged there.  York Hotel Interior With the cops closing in on him, Raymond left San Francisco and boarded a plane for Los Angeles. He booked a room at the Biltmore Hotel and stayed for a couple of weeks, then left without paying his bill. In wartime Los Angeles, Raymond would have found it very easy to disappear because the city was jammed with military personnel and civilian war workers. In fact, if it hadn’t been for eagle-eyed traffic patrolman and 20 year LAPD veteran Clarence Clarke, Raymond may have continued to fly under the radar, just like a German Messerschmitt. But this was not to be. Officer Clarke was directing traffic on Broadway near 7th in front of one of the movie palaces (not identified by name in the LA Times coverage), when he noticed that the doorman bore a striking resemblance to a young man he’d seen on a wanted bulletin.

York Hotel Interior With the cops closing in on him, Raymond left San Francisco and boarded a plane for Los Angeles. He booked a room at the Biltmore Hotel and stayed for a couple of weeks, then left without paying his bill. In wartime Los Angeles, Raymond would have found it very easy to disappear because the city was jammed with military personnel and civilian war workers. In fact, if it hadn’t been for eagle-eyed traffic patrolman and 20 year LAPD veteran Clarence Clarke, Raymond may have continued to fly under the radar, just like a German Messerschmitt. But this was not to be. Officer Clarke was directing traffic on Broadway near 7th in front of one of the movie palaces (not identified by name in the LA Times coverage), when he noticed that the doorman bore a striking resemblance to a young man he’d seen on a wanted bulletin.  Raymond Latshaw Acting on his hunch, Clarke approached the teenaged doorman. When Latshaw saw the cop coming towards him, he knew that he was busted – he didn’t even try to make a break for it. Identifying himself as the wanted man, he quickly confessed to the slayings. According to the shy and awkward killer, he’d snapped when he heard his father and stepmother arguing. He told LA Times reporters: “I was tending my rabbits when they quarreled. I went and got my father’s gun from the house, and shot him in the head.” Why, after shooting his father to protect his stepmother, did Raymond kill the other four members of his family, including his six year old half brother Charles? Raymond said that they were all witnesses, and he shot them to keep them quiet. Latshaw would ultimately plead guilty in a Northern California courtroom. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in San Quentin.

Raymond Latshaw Acting on his hunch, Clarke approached the teenaged doorman. When Latshaw saw the cop coming towards him, he knew that he was busted – he didn’t even try to make a break for it. Identifying himself as the wanted man, he quickly confessed to the slayings. According to the shy and awkward killer, he’d snapped when he heard his father and stepmother arguing. He told LA Times reporters: “I was tending my rabbits when they quarreled. I went and got my father’s gun from the house, and shot him in the head.” Why, after shooting his father to protect his stepmother, did Raymond kill the other four members of his family, including his six year old half brother Charles? Raymond said that they were all witnesses, and he shot them to keep them quiet. Latshaw would ultimately plead guilty in a Northern California courtroom. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in San Quentin.

Mr. Johnson’s Mickey Finns

George Brydon, resident of Sherman in the San Fernando Valley, was a prime rube, robbed twice before baring his shame to local police and newspaper readers. His sad tale began when he followed a man he knew as Johnson to a rooming house at 224 Winston, and shared two drinks with the acquaintance. Before long, he sank into the blackness of the drugged, and awoke much later, sans rings, watch and cash. Stumbling about seeking his lost goods, Brydon attracted the attention of friend Johnson, who returned with another man, and together they tied their victim’s hands with his own belt, forced him to swallow liquor, then administered a beating. Brydon again passed out, and awake to find he had now been relieved of his clothing, as well. Someone in a nearby room called for help, and after treatment at the Receiving Hospital, the unfortunate fellow borrowed a wrapper from a friendly cop and slunk home to sleep it off. If he came again to SRO Land, it didn’t make the papers.

Rescued from the Clutches of a Superhuman Diagnostician

After they left, Frank Martin presented Officer Smith with his card, as proof of his legitimate standing in the business community. It read as follows: “Frank N. Martin Diagnostician of Diseases by Superhuman Power. Can ascertain, locate and describe the disease of any patient without asking a question or even seeing the patient.”

Besides possessing power of superhuman dimensions, Frank Martin also possessed power of attorney signed by Mrs. Larkin, authorizing him to dispose of certain real estate in her name. And here the trail of Mrs. Larkin and “Dr.” Martin takes a decidedly racy turn. As it happens, Mrs. Larkin had come into property in South Pasadena after her husband abandoned her and her daughter. In order to stretch their income, Mrs. Larkin took in boarders at the South Pasadena residence, one of whom was Frank Martin. The couple engaged in intimacies of a closer nature than the usual landlady/tenant variety, relations Mrs. Larkin’s daughter referred to as hypnotism. In time, Mrs. Larkin became so impressed with Martin’s medical acumen that she planned to sell off part of her country estate and use the proceeds to go into partnership with him selling patent medicines. For this reason she granted Martin power of attorney, and visited him in his room on Main street. That she brought her combs and toiletries with her on her visit can only be attributed to the complex nature of their business dealings, which she anticipated would require her to spend the night downtown.

Under pressure from her daughter, Mrs. Larkin revoked the power of attorney, but since Martin had already sold the property, it was unlikely she was able to prevent him from banking the profits. Profits he undoubtedly used to further the pursuit of long distance diagnostics.

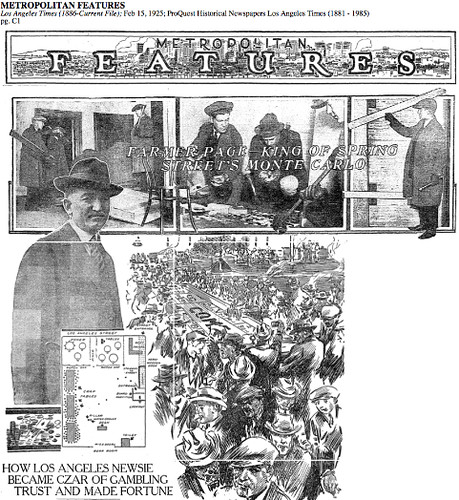

Spring Street’s Monte Carlo

What was SROland’s grandest gaming establishment? Milton “Farmer” Page’s El Dorado Club. “Farmer” Page was an unlikely gambling kingpin. His nickname came from “his shambling gait and ill-fitting clothes.” He dropped out of school at age 12. But Page was an enterprising fellow. As a newsboy, he secured the lucrative corner of Second and Spring Streets. There he developed a feel for the dice. Younger brother Stanley, a famous jockey, got “Farmer” off the street and made him his personal valet, but Page just took his dice and card games to the tracks. In 1917, he moved back to Los Angeles and opened a game in the basement of the old Del Monte bar on West Third Street. He soon gained a reputation as an “honest gambler.” By 1918, he had five gambling clubs. He was now ready for the big-time — the El Dorado Club. Occupying the entire top floor of a Spring Street office building, the El Dorado had a great run, hosting hundreds of devotees of poker, black jack, and dice games. Crowds of 500 or 600 people a night were common. When the police felt obliged to raid the aforementioned establishment, 15-20 “house men” would step forward to be arrested. Page would later bail them out of Central Police Station. Three months was a typical run, after which time Page would let the police shut things down and then move to another location.

But by early 1925, things looked bad for Mr. Page. He’d shot a man, in self defense, but the cops were watching him. Customers stopped coming. Now, murmur the “wise ones on Spring Street” the gambling trust is broken. But have no doubt, they say: a new combine will inevitably rise to replace it… We’ll see more of Mr. Page and such confreres as “Zeke” Caress, Bob Sherwood, Guy McAfee, Albert Marco, and Charles Crawford, as well as rivals such as Frank and Tony Cornero. We’ll also begin to explore the shadowy entity that controlled the Los Angeles underworld and that in time came to be known as “the Combination.”  Illustration credit: The Los Angeles Times, from the February 15, 1925 article, “Farmer Page—King of Spring Street’s Monte Carlo.”

Illustration credit: The Los Angeles Times, from the February 15, 1925 article, “Farmer Page—King of Spring Street’s Monte Carlo.”

The Case of the Missing Garter

When engaging a private detective, one seeks quick intelligence, discretion, the ability to negotiate all stratum of society with ease and elan. Based on an incident that occurred around noon on a Sunday in 1896, Joseph E. Gross is probably not your man. It seems the detective was standing with friends on the Southwest corner of Third and Spring, as a pair of fashionable ladies awaited the University Line red car trolley in the road. As one boarded, she gave a little wiggle of one foot and a tiny contraption fell onto the ground. Enjoying the spectacle of the wiggle, and wishing to be helpful and make a new acquaintance, Gross, snatched up the device and marched into the car, loudly calling to the lady who had lost it. He realized what he held about the same moment she did: a black garter with a silver buckle, which the dropper had intentionally allowed to fall rather than adjusting it in the street. “Yes, it’s mine, but you may have it,” stammered the embarrassed lass, and Mr. Gross jumped free from the car to allow Miss Saggy Stockings to roll on without him. Next stop: Humiliation!

The Fabulous Baker Broads

Main Street, 1916

Photo Credit: USC Digital Archives

Sometime after midnight on January 29th, 1915, Anna “Diamond Tooth” Baker and Mrs. Louise Baker were arrested in a rooming house at 652 1/2 South Main Street. The sisters were among 54 women apprehended by police that night as the department pursued a wholesale clamp down on vice in the downtown area, authorized by the recently passed Red Light Abatement Act. The Act aimed at stemming prostitution by targeting the real estate used for this purpose, as well as property owners, property managers, and renters. As a result of this legislation, landlords would often refuse to rent to single women. In some cases, single women were prohibited from owning property at all in downtown neighborhoods of American cities.

On January 29th, police raided forty houses. They posted plainclothesmen at all exits to the houses, while officers rushed in and detained anyone within the premises for questioning. The bookings broke all records in the female department in City Jail. Many of the women were forced to stand in the halls until more cells were converted for female use.

At a hearing on March 27th of that year, a temporary restraining order was issued against Louise Baker, the proprietor of the rooming house on South Spring, forbidding her from conducting business there on the grounds that the house was being used for immoral purposes. When the landlord and property owner of 652 1â„2 South Main, who were also facing charges, claimed they had no knowledge of Mrs. Baker’s activities, the prosecution presented depositions from three police officers which called their statements into question. The officers testified that Mrs. Baker’s “resort” was one of the most notorious of its kind in Los Angeles, and alleged that Mrs. Baker boasted to them that she had “cleaned up more than $40,000 in Los Angeles” and that she would “use that amount to fight the police force, if necessary.”

This was not the first time Mrs. Baker’s words were used against her in court. In October of the previous year, Louise Baker was cited in contempt of court for talking too much. “Unable to stem her voluble flow of language”, the judge told her “to talk to the bars.” She was sentenced to a day in jail, but as her trial concluded at 4 pm and the prison workday ended at 5, she was able to fulfill her sentence in one hour. As it happens, Mrs. Baker was in court to accuse Lou Haufbine, a furniture salesman, of disturbing the peace. Although Haufbine was found guilty, he received a suspended sentence, while Mrs. Baker was marched off to jail. After serving 60 minutes worth of hard time, Mrs. Baker apologized to the court. “I wanted to be heard,” she said. “I guess I talked too much.”

Her sister, Anna “Diamond Tooth” Baker, known for the half-carat diamond she wore in a front tooth, generally faired better in court. Prior to her arrest in 1915 she was acquitted of several charges of conducting a house of ill repute at nearby 610 1/2 Spring Street. Each time Anna requested a jury trial, and each time jurors found her innocent, declaring that she couldn’t possibly be as bad as she was represented to be. On one occasion, however, Miss Baker was unable to make an appearance at court on the designated day, and called Police Judge Chambers to request he change the date. Judge Chambers told her that his court “had not been so modernized that its sessions were held over the telephone, and unless she put in appearance her bail of $200 would be forfeited.” After Anna failed to appear, the judge issued a bench warrant, and raised the bail to $500. Louise came to her sister’s aid, and, “after expressing her indignation,” (we can only assume at great length) bought her sister’s freedom with a large pile of silver dollars, gold coins, and greenbacks. Anna, apparently equally as voluble as her sister, commented to reporters that she could buy automobiles, so why should she not purchase her own liberty when it cost a mere 500 clams?

Spring Street looking South from 6th, circa 1915

Photo credit: USC Digital Archive

Mad Dogs and Angelenos Go Out in the Noonday Sun

Jack Vernon, resident of 245 1â„2 South Spring Street, was one of several hundred Angelenos to fall prey to the scourge of rabies which periodically struck downtown Los Angeles and its suburbs in the early part of the century. Thousands of rabid cats and dogs roamed the streets, attacking babies, school children, and adults. One Sunday during this outbreak a group of handsomely gowned women on their way to church sought safety from a charging mad dog by scrambling up the cliff side entrance to the Broadway Street tunnel, where they remained until a shotgun-toting policeman came to dispatch the menacing beast.

The first case of rabies during this period was recorded in Pasadena, where local health officials quickly passed an ordinance requiring pet owners to muzzle their dogs. The muzzle law brought a halt to the spread of the disease in that city, but it proved unpopular in Los Angeles, and after one week, was revoked. Members of the city health board objected to dedicating police manpower to enforce the ordinance, and residents protested the inhumanity of restraining man’s best friend in such a brutal way. No measures were taken to combat the epidemic downtown until tragedy struck a prominent city family. A few days before Christmas, 10 year old Joseph Scott Jr. went out on his front lawn at 984 Elden Street to eat a piece of bread and butter, when a stray dog jumped the fence and nipped him in the leg. As health officials were still in denial about the rabies threat in the city, they hadn’t raised an alarm, and the child’s family saw no reason to take extra precautions over such a minor dog bite. It healed over quickly. Six weeks later, the child became violently ill, and died in agony that night. His father, Joseph Scott, was president of the Los Angeles Board of Education and also President of the Chamber of Commerce. In his grief, Scott made every effort to draw attention to his son’s death, hoping it might save lives.

Likely alerted to the rabies danger by the publicity surrounding Joseph Scott Jr.’s death, Jack Vernon sought treatment in January for a dog bite at the Receiving Hospital at Hill and First Streets. A nurse poured carbolic acid into his wound and cauterized it, a very unpleasant business. It was routine to inform bite victims that rabies can lie dormant for up to three years, so Jack probably faced the dilemma of either having to track down the animal that bit him to confirm the rabies diagnosis, or waiting years before he could be sure he wouldn’t one day form a violent aversion to water, leap at his loved ones throats and suffocate to death from respiratory paralysis. The only other option at the time was to travel to the Pasteur Institute in Chicago, which had recently pioneered a rabies serum.

One Angeleno who sought the Pasteur cure after being bitten by a mad dog found little consolation in the treatment. He was on a train traveling back to Los Angeles, when, according to his fellow passengers, he suddenly stabbed himself repeatedly in the throat with a pocketknife. He stated later from his sickbed that his mind had given way under the worry that he might go mad, and had decided suicide was his only way out.

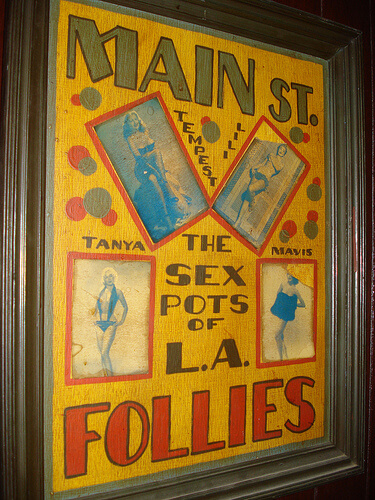

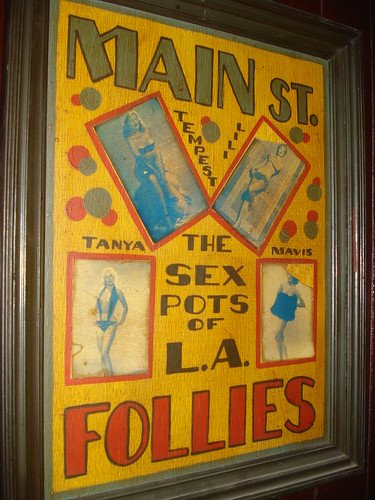

When Legends Collide: Lili St. Cyr and Tempest Storm

Lili St. Cyr was a marquee burlesque striptease star known for her bubble bath routine. Tempest Storm who went onstage just before St. Cyr referred to herself as a performer so green that she didn’t know her right foot from her left. But Ms. Storm’s assets and the threat she posed to the headliner didn’t go unnoticed by St.Cyr. While Ms. Storm performed onstage, St. Cyr would watch her like a hawk and point out any similarities in their acts to impresario Lillian Hunt. One night another dancer who performed earlier in the show dropped a pin onstage. Whereas most dancers used hooks or zippers for their costumes, this dancer used pins. The barefoot St. Cyr stepped on the pin and when she finished her number she was livid and accused Ms. Storm of leaving the pin behind. Ms. Storm a fiery redhead with a no nonsense attitude quit on the spot. As she was packing her bags, the quick thinking Lillian Hunt came up with a solution. She offered to send Ms. Storm to the El Rey Theater in Oakland to perform as the headliner. From that point on, Tempest Storm never looked back and her star shone brighter and brighter. She called it one of the luckiest things that ever happened to her. Fast forward nearly twenty years. The two women hadn’t crossed paths since that incident at the Follies Theater. Ms. Storm had just finished headlining the Minsky’s Revue at the Aladdin in Las Vegas. Lili St. Cyr came in to headline the next night. Storm’s daughter Trish wanted to meet Lili St. Cyr. Ms. Storm wasn’t sure at all what to expect but when they went backstage, St. Cyr welcomed them inside and graciously said, “I knew you were going be a star.” Storm’s response, “Is that why you bitched about me?” That was all it took. The two legends of burlesque shared a laugh and became fast friends. After St. Cyr retired from performing, Ms. Storm sent her money from time to time and they remained in contact up to St. Cyr’s death in 1999. At the reopening of Cole’s just down the block from where the original Follies Theater once stood a faded burlesque billboard hangs in the corner near the bar. The two burlesque divas Tempest Storm and Lili St. Cyr almost look as if they were destined to face off at that moment in time.