Introduction to Eva Dugan

Born in 1876, Mrs. Eva Dugan somehow managed to survive a hard-scrabble childhood to become an adult with few skills, and even fewer expectations. In photographs, Eva seemed to always have a tentative expression on her face, as if she were waiting for the other shoe to drop – and inevitably, it did. She had been married at sixteen, and bore two children. Eva’s husband abandoned her and the kids, so she turned to prostitution to make ends meet.

By January of 1927, Eva was in her early 50s and working in Arizona as a housekeeper for Mr. Andrew J. Mathis, a wealthy reclusive rancher. Mathis was demanding, cranky, and cheap. Mathis and Eva butted heads frequently during the two months that she was in his employ. Mathis even accused Eva of trying to poison him! An acquaintance of Mathis’ said that he’d been present when the man had finally given Eva her walking papers. Mathis had told her in no uncertain terms to leave the ranch and never return.

A few days after his friend had overheard him banishing Eva from the ranch forever, a group of Mathis’ neighbors reported him missing. The neighbors had become suspicious when Eva offered to sell them some of Mathis’ livestock. She claimed that Mathis had departed for California, and had turned all of his property over to her. A notorious tightwad, Mathis wasn’t a man who would have willingly turned over his property to a woman who’d only worked for him for a couple of months.

Not long after Mathis went missing, Eva also vanished. A search of the ranch by local authorities didn’t turn up a body, but they did find some troubling clues. An ear trumpet belonging to the hard-of-hearing Mathis was found in a small stove in the front room of the ranch. Carelessly discarded clothing and bits of automobile equipment, including a blood-stained cover for a roadster, gave cops little hope that the rancher would be found alive.

It was months before Eva was finally discovered living in White Plains, New York. Returning to Arizona to face auto theft charges, Eva was convicted. The judge sentenced her to a three to six year term in the state penitentiary.

Nearly a year after Mathis had disappeared, a camper on the property near the ranch noticed an odd depression in the soil. The camper scraped away some of the topsoil, and after a minimum of digging he unearthed the skeleton of a man. Tattered clothing and hair on the skull indicated that the body discovered in the shallow grave was that of A.J. Mathis.

Once Mathis’ body had been found, Eva had some explaining to do; however, she preferred denials to explanations. She told cops that if she had been responsible for Mathis’ death and subsequent burial, she’d have buried him deep enough so that he’d never have been found. Far from convincing, her denial sounded more like a woman trying to extricate herself from a capital murder charge than one proclaiming her innocence.

Eva finally settled on a story and stuck with it. She alleged that she’d met a young man named Jack outside of a local restaurant. The two started a conversation, and Eva told him that he could get a job on Mathis’ ranch.

Jack went directly to the ranch, where he was employed on the spot. Unfortunately, his first day on the job didn’t quite turn out the way he had planned. Maybe things would have been different if Jack had known how to handle the basics. Mathis’ took umbrage when Jack failed to milk a cow as he’d been directed. Mathis complained: “If you can’t milk a cow, what the hell are you good for?’’ Mathis struck Jack. The young man quickly recovered from the blow and hit Mathis, who fell to the ground and did not get up.

Eva insisted that she and Jack had tried unsuccessfully to revive Mathis. She also claimed that she wanted to go for aid but that Jack told her if she didn’t help him get Mathis’ body into the car so he could dispose of it, he’d leave her to face the music on her own.

Eva’s story had more than a few holes in it – the biggest one being Jack. Not everyone was convinced that the young man had ever actually existed, because only one person was ever found who could corroborate Eva’s statement.

Just as Eva was being charged with A.J. Mathis’ murder, a young dark-haired young man was confessing to a grisly child murder in Los Angeles. The young man was the infamous slayer, Edward Hickman (aka “The Fox’’). Hickman had kidnapped, murdered, and dismembered twelve year old Marion Parker.

Arizona investigators began to suspect that Hickman had been “Jack’’ in Eva’s story. Hickman stated that he’d been in Phoenix for a few days prior to Mathis’ disappearance, and that he’d also been in Kansas City during the same time that Eva said she’d dropped “Jack’’ off in that city on her way to New York.

When Eva was shown photographs of Edward Hickman, she said that she thought he and Jack were one and the same but that she wasn’t absolutely certain.

Even if Eva had been sure about the identity of Edward/Jack, LA cops were not about to allow anyone to interfere with murder charges against him. Although Hickman was never charged in the Mathis case, “The Fox’’ was hanged for Marion Parker’s murder on October 19, 1928.

Eva was tried and convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to death. The only thing that could have saved her from execution would have been a successful insanity plea. Two doctors testified that her mental state had been compromised due to the “inroads made by a disease she contracted more than 30 years ago.” Eva was syphilitic. Despite the medical testimony, a jury determined that Eva was indeed sane, and plans for her execution continued.

Because she had no wish to be buried in the prison cemetery, Eva made and sold embroidered items so that she would have enough money to pay for a proper burial. She also wired her father and asked him to send her $50 to help pay for her funeral.

As the date of her execution drew nearer, Eva asked the Warden what she should wear to her hanging. He advised her not to wear any of her best things, so the handmade, lovingly embroidered silk shroud she’d created for the occasion was set aside to be used later for her burial.

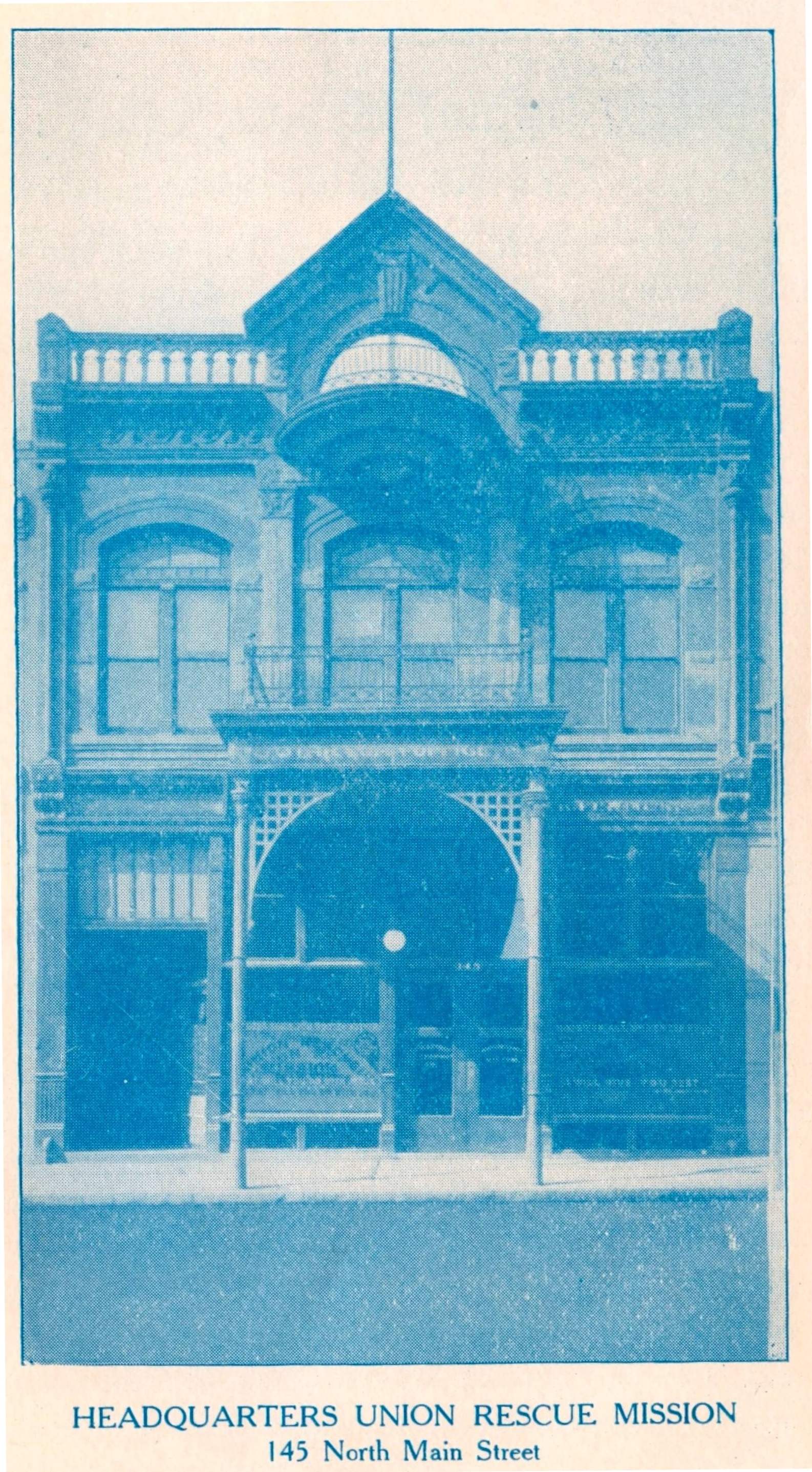

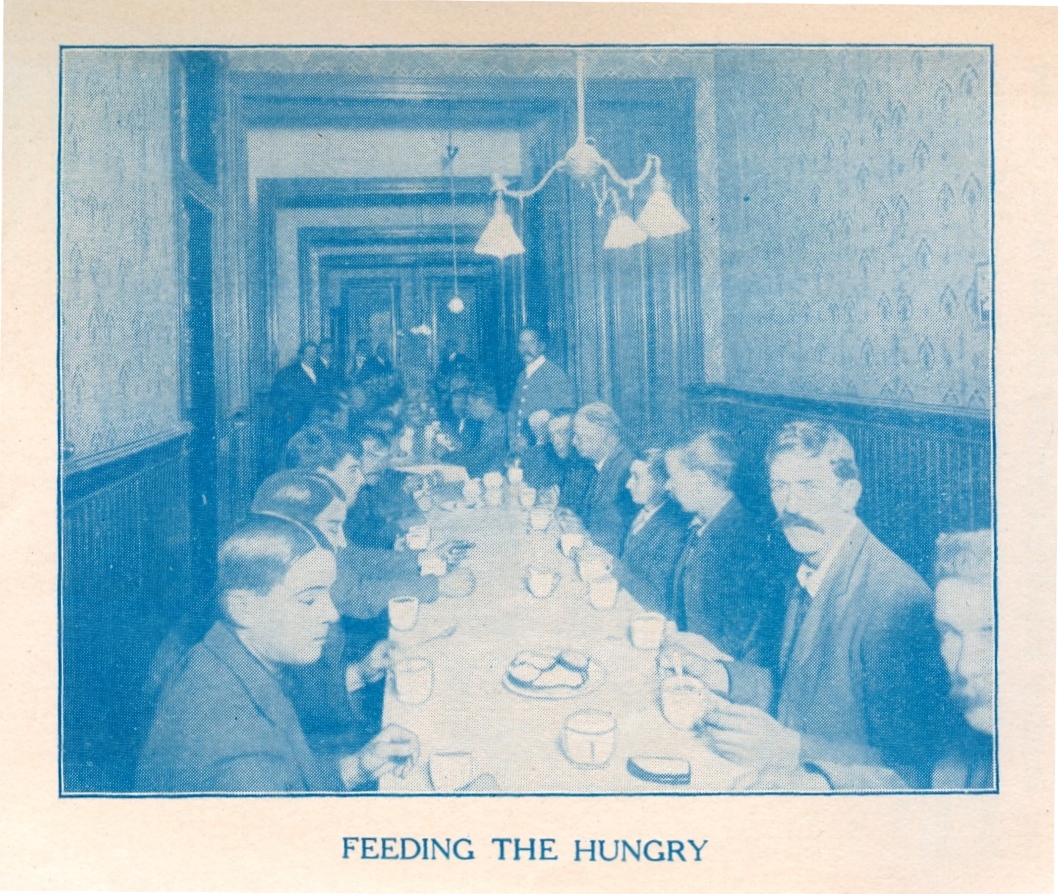

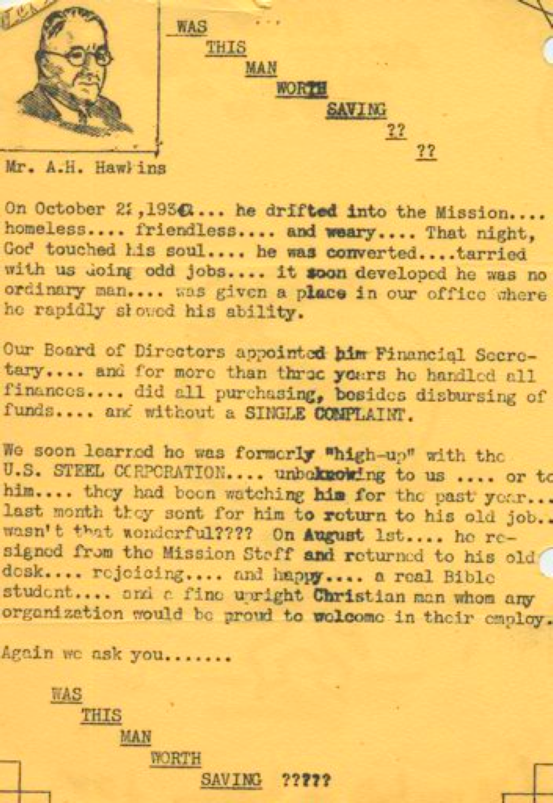

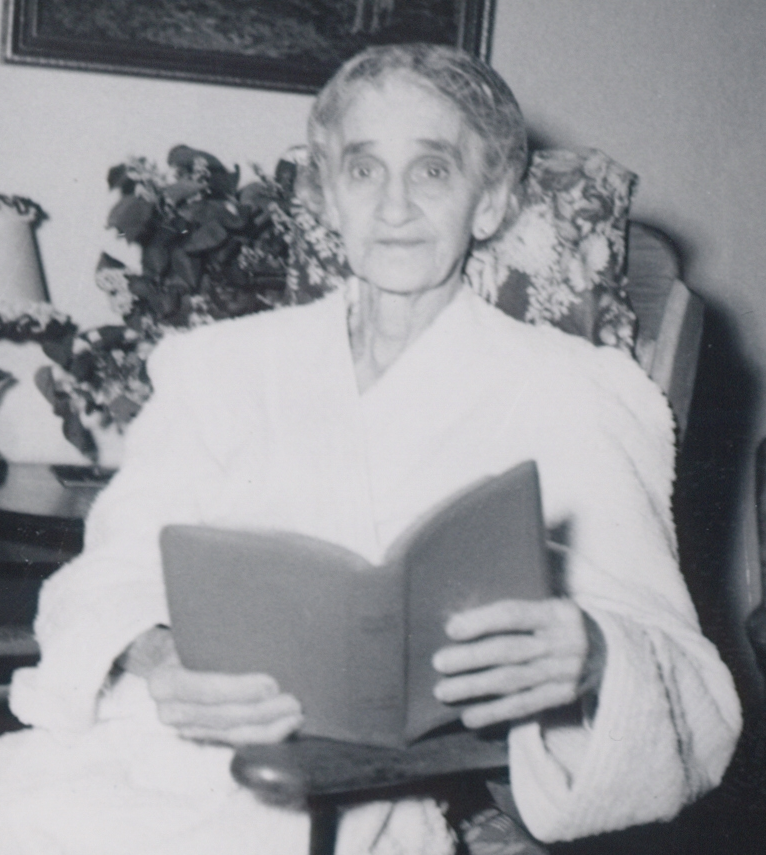

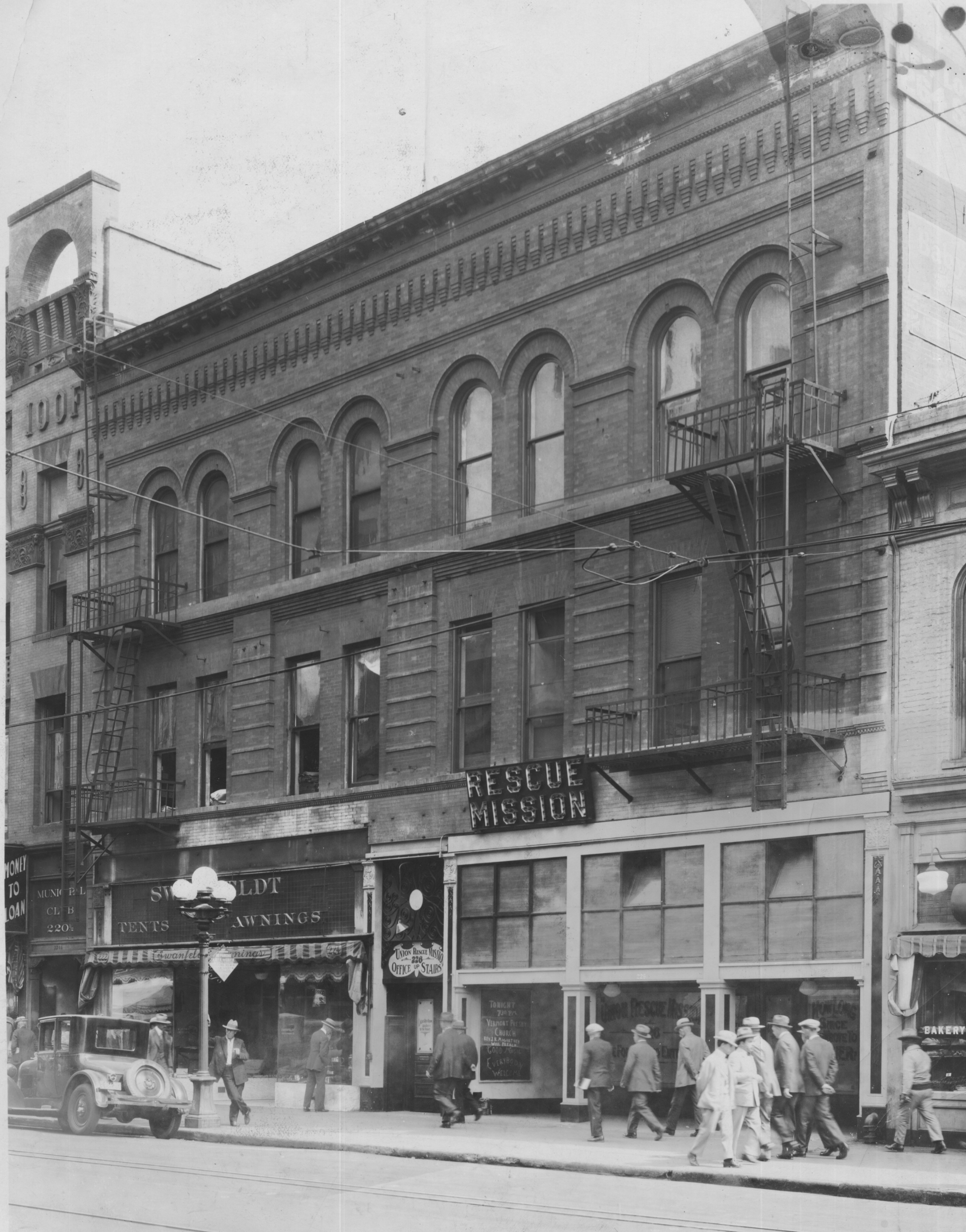

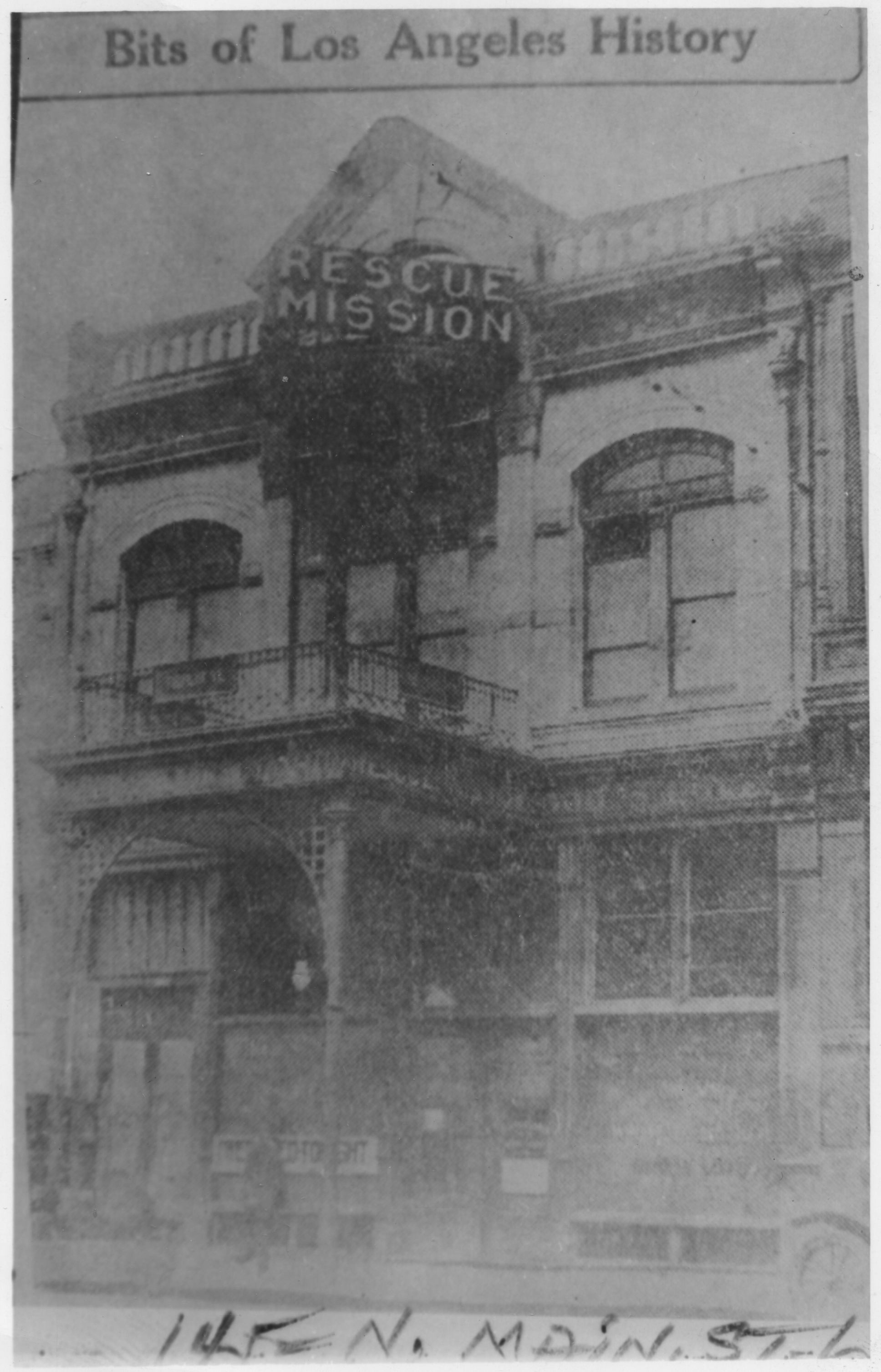

It was during the long hours leading up to her hanging that Eva was visited by Mother Benton from the Union Rescue Mission in Los Angeles. Mother Benton believed that Eva’s soul had been saved as a result of their prayers.

Eva remained stoic as she walked to the place of her execution. She even recited an ironic bit of doggerel:

“We came into this world all naked and bare; Where we are going, the Lord only knows where; If we are good fellows here; We’ll be good fellows there.’’

As it turned out, it was fortunate that Eva took the warden’s advice and didn’t wear her handmade silk shroud to the hanging. Due to a miscalculation on the executioner’s part when she fell through the trap at the end of a rope, her neck wasn’t broken; she was decapitated! Eva’s head rolled within a few feet of the 60 witnesses – all of whom fled in terror.

On February 21, 1930, Eva Dugan was the first – and last – woman to be legally hanged in the state of Arizona. Three years after the horror of Eva’s botched execution, Arizona switched from the rope to the gas chamber.

Eva Dugan’s Testimonial

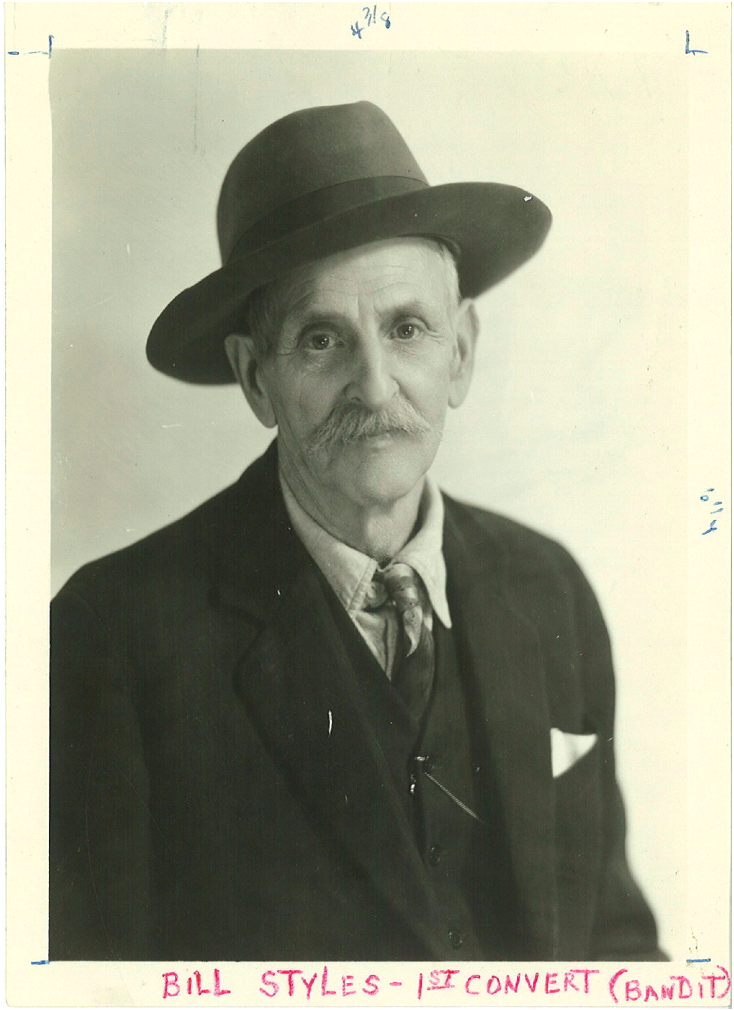

Mission Mother [Mother Benton] prays with a notorious murderess in Arizona and believes god saved her soul. Apparently she remembered one hymn that she sang as a girl in sunday school and that hymn was “Shall We Gather At the River”.

Copied from LA Times Feb. 21, 1930

Poison given up by Mrs. Dugan as end nears. Slayer of employer recites doggerel and sings on death march.

Florence, Arizona. Feb. 21

Marching to her death with a firm step, and with never a show of emotion or breaking, Mrs. Eva Dugan, 52, was hanged here at 5:02am for the murder three years ago of J. H. Mathis, aged Tucson rancher, whose housekeeper she had been. To quote one of her guests, Mrs. Dugan “died like a man.”

When the trap was sprung the first impact of the knotted rope snapped Mrs. Dugan’s head from her body. She was the first woman to be legally executed in Arizona.

Collapse Expected

For use in case the woman collapsed four boards had been provided with which she was to have been strapped upright on the gallows, but they were unnecessary. Only the customary four leather straps were placed about her legs.

Given an opportunity to make a final statement as the back cap was adjusted, she merely shook her head to the negative.

Warden Wright clasped her hand.

“God bless you, Eva” he said.

“Good-by, Daddy Wright,” she said. Those were her last words.

Recites doggerel

The death march was accomplished quickly. as she walked to the execution chamber between two guards with her face set in a grim smile, Mrs. Dugan recited a bit of doggerel:

“We came into the world all naked and bare, where we are going, the lord only knows where, if we are good fellows here, we’ll be good fellows there.”

A sensation was created by the woman a short time before she was taken from the death cell when she voluntarily surrendered to her two women guards a safety razor blade and a small phial presumed to contain poison.

“Well, what do you thing it? Would your wait for the rope?” she remarked as she delivered the bottle and the keen bit of steel, indicating that she had considered cheating the gallows but had decided to let the law take its course.

Her request that she be given “one last pint of prescription whiskey” had been denied by prison authorities.

The execution was witnessed by approximately 100 persons who crowded into a small chamber that provided adequate accommodations for only 50.

Mrs. Dugan remained awake during all of her last night on earth, in company with the prison chaplain and a few friends from outside the prison and another woman prisoner.

Ignores death watch

Apparently she was unmindful of the death watch that paced firmly pack and forth outside her cell, while the hands of the clock raced toward the fatal hour when she was to pay her debt to society.

At Mrs. Dugan’s request she and her guests were served orangeade.

There was no outbursts of emotion from the doomed woman when Warden Wright and his assistants called at her cell this morning summoning her to begin the solemn death march.

She lighted a cigarette and inhaled deeply as she passed the corridor and joked with the guards as the party neared the execution chamber.

It was a leaden morning and a light rain was falling in the bit of open courtyard through which she was lead from her cell into the death house.

Sings on march

Mrs. Dugan apparently was trying to appear to be in higher spirits than any other member of the group. “I don’t know where I’m going, but I’m on my way,” she sang as she crossed the courtyard.

Two of the women guards in the party left her at the door and she affectionately kissed them a last goodbye.

“I love everyone connected with this prison,” she said. “You have all been good to me and I can’t blame you for what the law is going to do to me.”

Then she walked firmly up the 13 iron steps to the death trap, said her last farewell to the warden Wright, and in a few moments her life was a closed book.

In the small prison plot behind the frowning grey concrete walls of the penitentiary Mrs. Dugan’s body will be buried with scant ceremony at 3’o clock this afternoon, it was announced by the ward.

She will have a better coffin then those provided the State of Arizona for hanged murderers, for by her sale of bead work, and by collecting 50 cents a piece from each of her visitors in the condemned cell, Mrs. Dugan raised the money to purchase a more elaborate casket.

Mrs. Dugan left instruction to send her trunk and her few small personal belongings to a cousin at Westin, Mo.

Among numerous telegrams and letter received by Mrs. Dugan at the condemned cell was a telegram from her daughter, Mrs. cecil lovelace, new york musician.

The telegram, dated South Bend, Ind, said: “My dear Mother: Be brave. God is with you. ALl my love. I will pray for you.”

Gold Rush Tale

A hitherto unrevealed chapter in Mrs. Dugan’s life came to light last night when she received from Seattle, washington a telegram signed by Ada Hostapple. It read:

“you have my admiration and sympathy for your grit and courage in this, your hour of greatest trouble.”

Mrs. Dugan said that she and “Ada” where “pals” during the gold rush in the Yukon.

Mrs. Dugan seemed to enjoy a “kick” at a farewell “party” with newspaper men last night. She called one of them “big boy” provided by cigarettes and cigars.

A rainbow over the arizona desert sunset brought tears to her eyes last night but her stoic calm otherwise was undisturbed as during the hour this morning when she was led slowly up the steps to the end of the rope.

She ate a dozen fried oysters and two boiled eggs last night. Her oder of three T-bone streaks and two lamb chops for breakfast this morning remained untouched.

By Pacific Coast News Service

Ceres, California Feb. 21—Alone in his little cottage here, William Mcdaniels, 82 year old father of Mrs. Eva Dugan, today received the news that his daughter had been hanged in Arizona for murder.

McDaniels had given up hope that she would be saved from the gallows, but his grief was uncontrollable when word of the Florence hanging reach him.

“She was innocent of that crime,” he declared. “They have hanged an innocent woman. I don’t think she was quite right in her mind, but I know that she did not commit murder.”

Neighbors tried to comfort the aged man, but he sent them away.