He triumphed over a gaggle of LA’s most prominent legal minds, only to be undone by a second rate mentalist with a trumped-up Teutonic alias. Shortly after establishing a law practice in Los Angeles, young George D. Blake, Esq. landed one of the city’s most sensational divorce cases, Mayberry v. Mayberry. Mr. Mayberry, an original California pioneer and prominent landowner, possessed an estate valued at more than a million dollars. In 1899 his wife brought suit against him for divorce on grounds of extreme cruelty and adultery. George D. Blake represented Mrs. Mayberry in a bitter trial that lasted several weeks. Despite employing four separate law firms in his defense, amounting to a team of every well-heeled lawyer in town, Mr. Mayberry was found guilty of acts of atrocious cruelty towards his wife, who had become a paraplegic as a result of a beating her husband administered to her during one of his many violent rages.

But George Blake’s reign at the top of the LA legal establishment lasted only a few short years. After the tragic death of his wife, Blake sought out spiritualists who promised to put him in contact with his departed spouse.

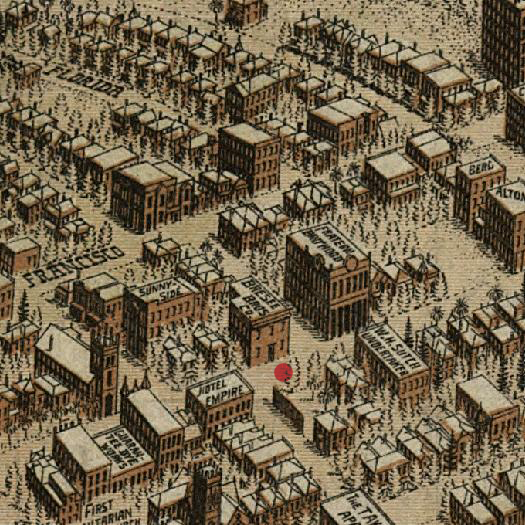

In 1904 he became especially close with one medium, Maude Von Freitag, a slate-writer who often plied her mind-reading trade at regular séances in Harmonial Hall at 125 West Fifth Street. During one of these events local authorities caught her sneaking peaks at folded slips of paper she alleged she could read without opening.

Attorney Blake, unperturbed by rumors of Von Freitag’s fraud, or by ample evidence of her fondness for liquor and morphine, took up with her with a passion, truly a passion, and accompanied her on a series of out of town trips of many days duration. Von Freitag’s husband and two children did not accompany them on these spiritual journeys.

In the fall of that year, Blake suffered a mental and physical breakdown, and spent weeks in the care of physicians at California Hospital. From there he went on to recuperate at a sanatorium near his mother’s house in Pontiac, Illinois, where he reunited with a childhood love, May Babcock. When he returned to Los Angeles in January of 1905, Miss Babcock accompanied him. But Maude Von Freitag still doted on her fellow spiritual traveler, and when she fell ill in March, she contacted Blake. Within the week the dashing Miss Babcock had packed up and headed back to Pontiac, Illinois.

George Blake took on the cost of Von Freitag’s care at a private hospital at no. 513 East Twelfth Street, and at Von Freitag’s urging even went so far as to try to obtain a loan for $5,000 dollars, in order to take part in a grand scheme involving millions of dollars, a complicated arrangement meant to insure the lifelong financial support of Von Freitag and her family. But the loan didn’t go through. At this point Von Freitag, likely sensing her influence over Blake might soon wane again, pulled out all the stops. In early April, she invited Blake to her sick-room, where she told him she would soon “pass-out” of this life, and asked that he lie down next to her on her bed to have one last talk about her approaching death, the mortgage of certain properties, and the future of her two children. During this conversation, as Blake later described to a friend, Von Freitag spoke to him of “high forces” and “lords of Karma”, she called herself Theodora, and explained to Blake that when she succumbed to death her soul would fly out of her body and into his, to be with him always, until he too passed out of the life, whereupon they would both sweep spiritward and dwell together on the astral plane. Von Freitag then fell into a fit of convulsions, and Blake let out a series of blood curdling screams that brought nurses and doctors to the door, only to find Blake in delirium, holding a limp Von Freitag in his arms. In the wake of subsequent events, shocked Angelenos surmised that Von Freitag placed Blake under a hypnotic spell of sorts during this visit, a spell that led directly to his ultimate loss of all hold on reality.

For three weeks after this episode, Blake managed to resume his law practice, but on April 24th, his frayed cord to reason snapped. While attending a performance at a Main Street theater he found himself possessed by a spirit and was compelled to lead the orchestra. The management didn’t care for this, and sent for the police. Later in the evening Blake was thrown out of a café for disturbing the peace. It seems the headwaiter was offended by Blake’s claim that he had assumed the genius and character of the late Emma Abbot, a famous opera singer of the past century. Blake spoke loudly to anyone who would listen about his plans to sue all parties involved in the fracas for 150 – 500 thousand dollars.

Blake then spent several days calling reporters to tell them of a suit he was pursuing to recover an English estate worth 64 million dollars. (Ah, Nigerian email-type schemes have always been with us!) He raved to the police officer assigned to restrain him of his appointment as “Most High Master”, working for the forces of good, in the name of which he and others like him would, tomorrow, at 9 o’clock, erect a bank at Third and Broadway, the most magnificent bank human eyes have ever conjured or human brain ever conceived… capitalized at 2 billion dollars, offering interest at 4%. He, Blake would be president, and would make pawnshops of the other banks, usurers that they are, charging 10 percent! A crowd gathered on South Broadway as Blake was escorted from his offices in the courthouse to an Olive Street Hotel, to await arrest and commitment to Highland Asylum for the Insane. Blake was taken to Highland on May 10th.

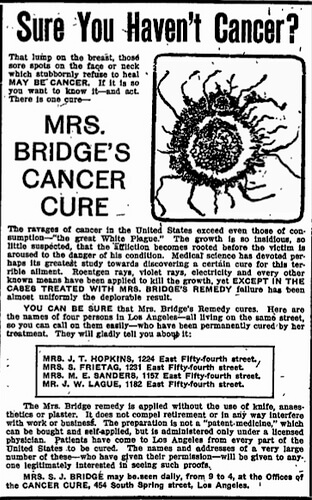

As for Maude Von Freitag, her story continued after Blake’s sad exit from sanity. Mere weeks after she claimed she lay at death’s door, Von Freitag experienced a miraculous recovery at the hands of an occultist colleague (or “sensation-monger spook” as the LA Times’ preferred to describe her). Von Freitag even returned to her lecturing career. The medium responsible for Von Freitag’s complete restoration to health offered to try her technique on George Blake, but was turned away at the door of the asylum.

George D. Blake, Esquire, never returned from Highland. He refused food and medical attention, and died there in November 1906, at the age of 43.