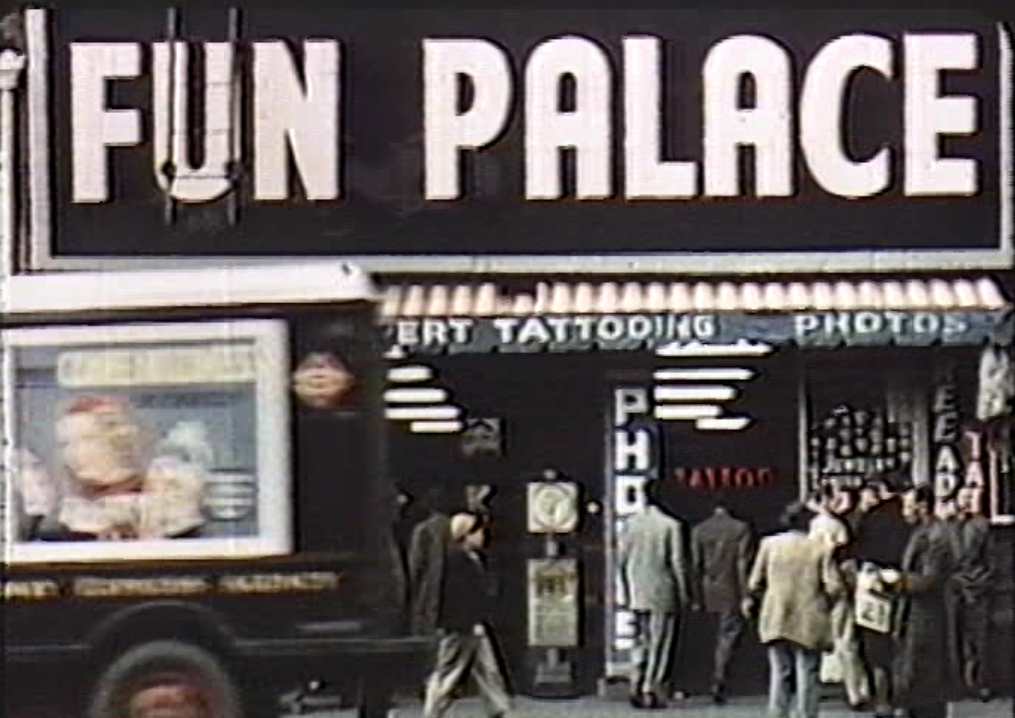

Suffice to say that conditions in my life were such that I apparently had nothing to tie to. After leaving the corporation I went with one of the independent companies and was successful in each territory assigned me to the extent that I did not have sufficient work to keep me occupied. Again drink became my master to such a measure that in the latter part of September 1930 I walked out of my office with the intention of going on a `tear’ until my money was gone and after that,—it just didn’t seem to matter what became of me,—I didn’t care to live. I am praising God that He over-ruled and led me to the Mission.

God reached down His hand in gracious mercy and through the blood of His Son cleansed what would have otherwise been another dreg in the social gutter. Today my feet are implanted on the solid rock of faith in our Lord Jesus Christ, and to me has come the ineffable peace which can only come from communion through Him to our heavenly Father, and in my heart is a song of praise for the power of God that reaches men through His Son.

The Lord has blessed me and kept me from falling back into the old habits. Now that I have a source of secret strength on which to draw in time of trouble and temptation I have my feet on solid ground. I have not taken a drink or even smoked since the Lord reclaimed me.”

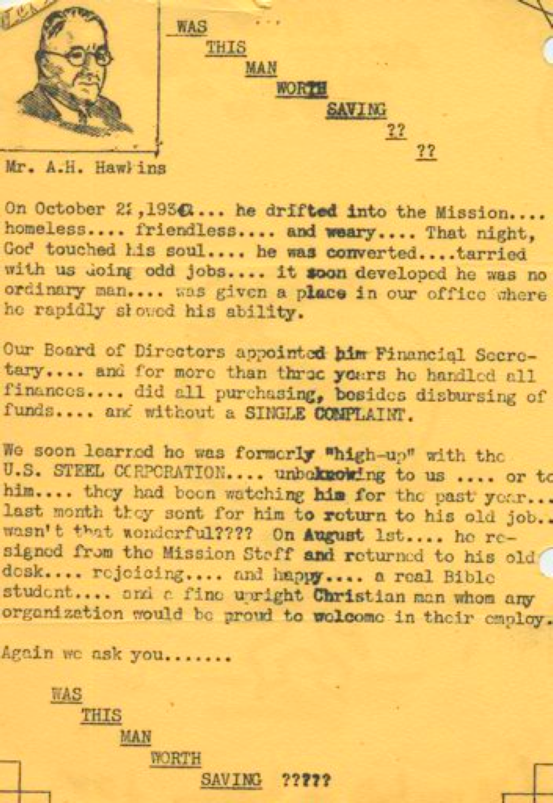

Excerpts from what others have said about him (Arthur H. Hawkins):

“His life was filled with a clear, ringing testimony for the Lord whom he loved and served. His personal daily contacts were a source of blessing to all within his reach. His faithful testimony pointed many to a saving knowledge of Christ, strengthened the faith of the saints, interested them in Bible study and support of the Lord’s work.”

XXXX

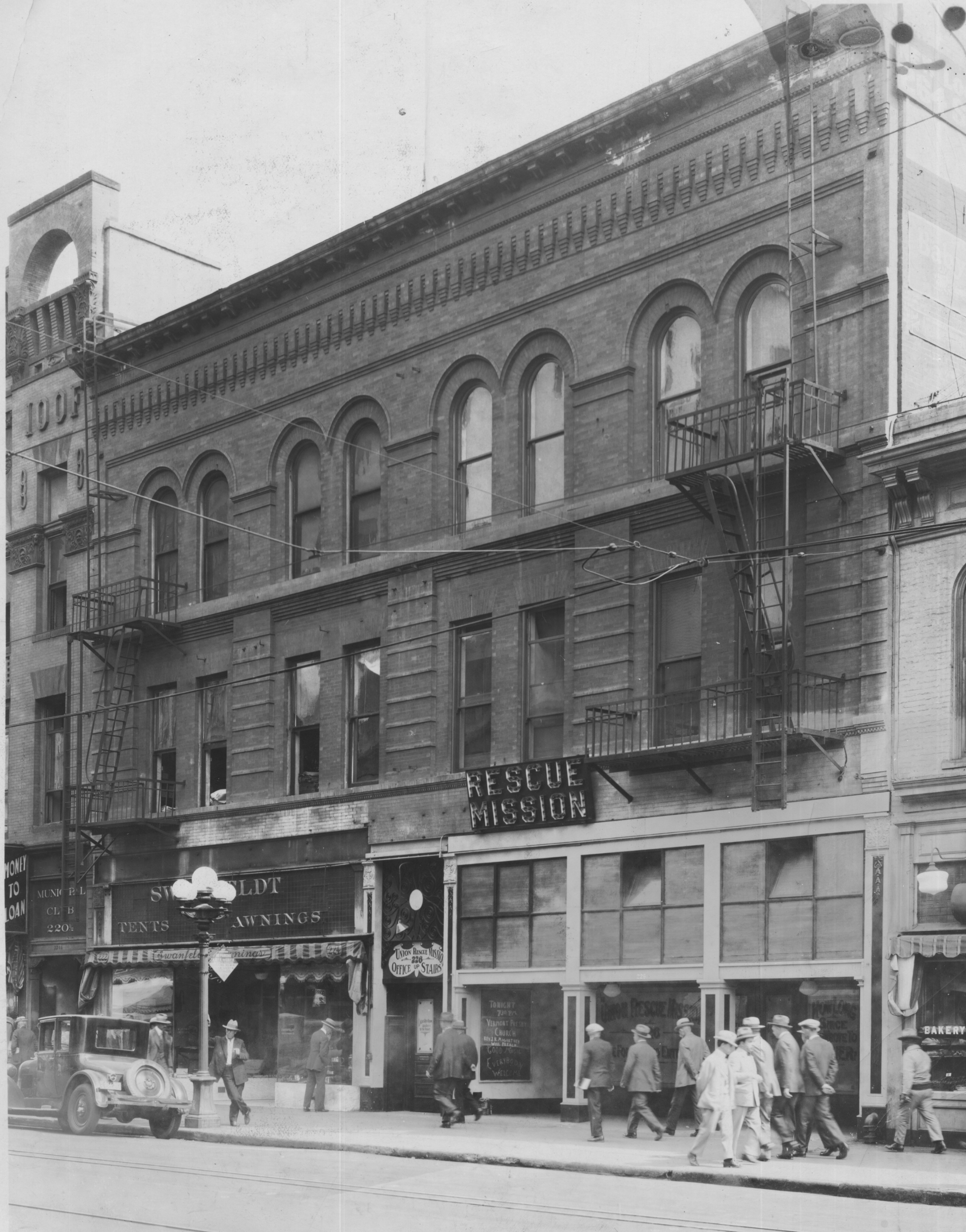

“Realizing his need of the Savior he attended a Mission service. When the invitation was given, he went to the altar and though much better dressed than the average business man, for he had earned a magnificent salary, there on his knees at the altar, brushing shoulders with the filthy, infested shambles of humanity from Main Street, he surrendered his heart and life to Christ. His clothing and the few possessions that he brought with him to Los Angeles were gladly shared with the Mission men until he was soon without sufficient clothing himself. He was a genuine conversion,—the Lord cleaned him up,—saved him to the uttermost, and filled him with the sweet fragrance of His love and made him a channel of blessing.”

XXXX

“He was in the steel business approximately 40 years, 35 of which were spent with the various subsidiaries of the U.S. Steel Corporation. He served 22 years in the Denver, Colorado office of American Sheet 7 Tin Plate Co. as Assistant Manager of Sales, where he received a silver service medal in 1927.

He was later connected with the Granite City Steel Co. where he served as Manager of Sales in both Memphis, Tenn. And Dallas, Tex.

Devoted four years to the URM.

Ten years ago became identified with the Los Angeles office of Columbia Steel Co., subsidiary of the U.S. Steel Corp., where he remained until the time of his death (Sept. 3, 1944).”

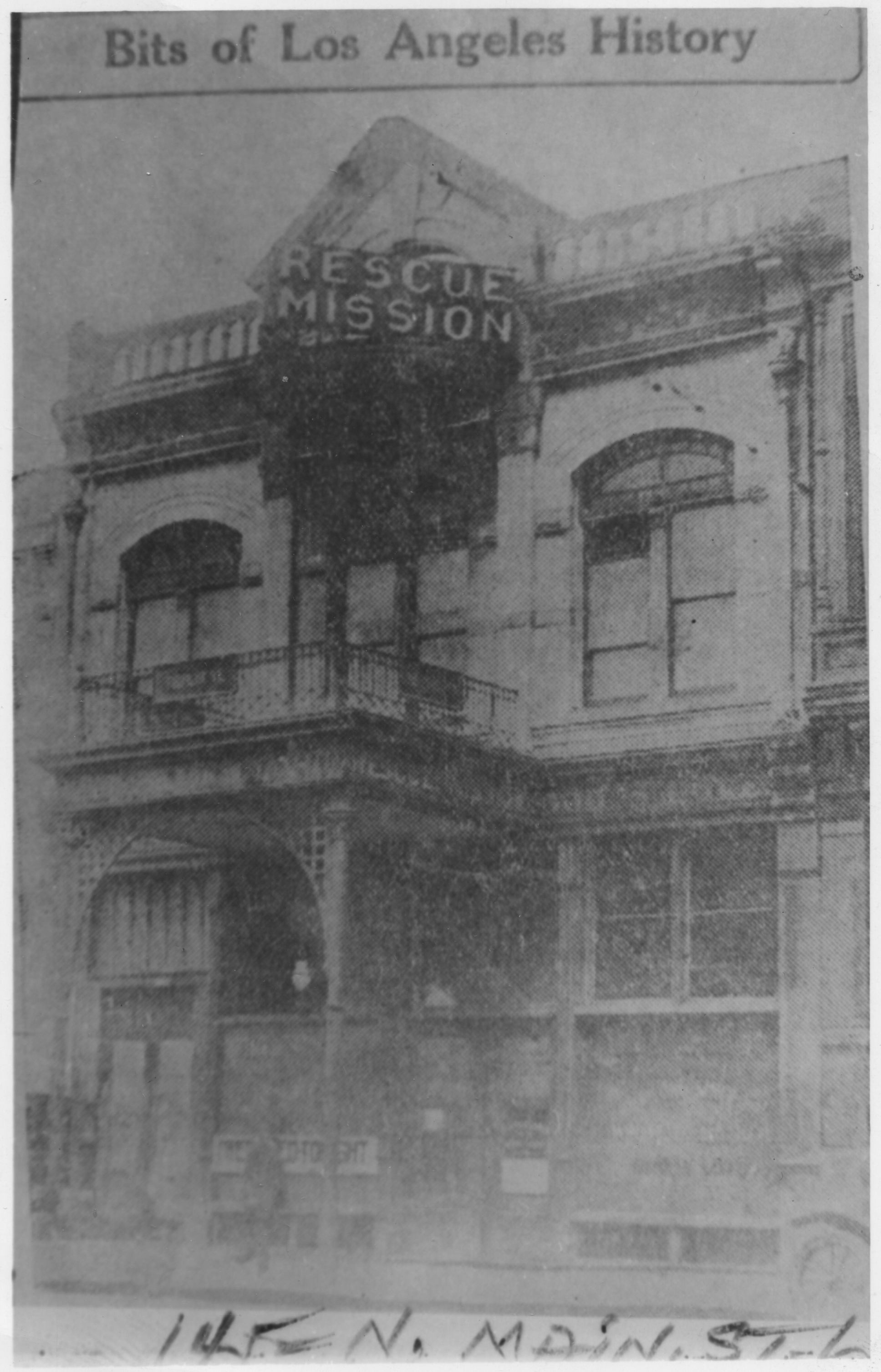

It is the story of Arthur Hawkins which is told in the film Of Scrap & Steel, which will be screened on the roof of the Union Rescue Mission on Thursday evening.