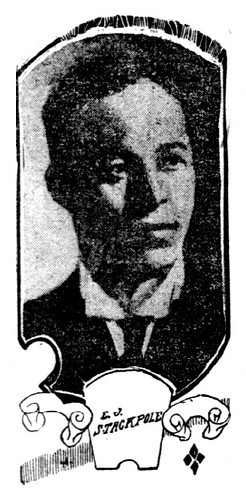

Aurellia Scheck, a 19-year-old laundry girl, loved Ernest Stackpole, a handsome, well-off young man, ten years her senior, who had come to Los Angeles from out east and rented a room in her mother’s boarding house. Together, she and Ernest plotted to murder Aurellia’s husband Joel, a plumber, so that they could collect the $500 for which his life was insured.

On June 14, 1906, Aurellia let Stackpole into the bedroom at the rear of 524 San Julian street where Joel lay sleeping, and Stackpole shot Joel – once in the heart and once straight through his forehead.

Aurellia claimed that two burglars had fired their pistols when Joel woke up and surprised them. The police didn’t believe her, not least because armed burglars were rare in the San Julian street area in those days, there being little worth stealing in any of the dilapidated houses.

The lovers were arrested and Aurellia soon cracked under interrogation, turning state’s witness in exchange for immunity from prosecution. After a trial that occupied the front pages of the city’s newspapers that summer, Stackpole was sentenced to life imprisonment, and Aurellia was remanded in custody on a charge of perjury, which never came to trial but which kept her locked up for three months.

Shortly before her release from the city jail, a Los Angeles Herald reporter secured the only interview that she ever gave the press, in which she spoke about her awful life and how she had become involved in murder.

Understandably, the interview differs to a large degree from her testimony in court. In order to condemn Stackpole, she had had to damn herself, too, by describing in detail the murder plot and her part in it. Speaking to the Herald’s reporter, she naturally tried to distance herself from the crime. Also, although the article claims to report Aurellia’s actual words, they were obviously prettied up by the journalist, as they lapse occasionally into the purplish and melodramatic language that was a mark of the paper’s feature pages.

Still, her story is worth reading, not only for the insight into the mind of a woman who got away with murder but for the glimpse of a life that, in its early particulars, is probably similar to the lives of many of those who drifted west in the early 20th century, heading for the bright lights and dark streets of SRO land.

“It won’t take long to tell all I know about myself,” Aurelia said. “I haven’t been on earth very long, and while things have happened rather rapidly in my life this last trouble has so far overshadowed them all that I can think of nothing else.

“I was born in lowa not quite twenty years ago. My mother and father separated two years after my birth, and after that I travelled about with my mother and sister.

“My mother was a nurse of experience and she made a good living that way until she met a man whom she thought she loved.

“At any rate they married, and from that time on I begun to realize what the world really was. We lived a gypsy life, travelling day and night through the hills and woods of Missouri, Arkansas, lowa and Nebraska.

“It was beg for food in the day time and sleep about a camp fire out in the woods at night.

“Strange fancies came to me then in those wild surroundings and I feared the dark, feared the shapes and shadows of the smoke from the camp fire and wondered what the world was made for and why we were all living on it. I have thought those same thoughts lying in my cell over there, with some woman of the town snoring off a drunken sleep within a dozen feet of me, and I have never found an answer to it.

“At last, my mother separated from my father. Their last quarrel was as violent as the life had been. I can see my mother now, pointing across the Missouri river to the far bank and my father slowly trudging toward its shadowy forests. That was the way they parted, and then we came to California.

“I was 11 years old then, and I managed to get one year’s schooling, then it was work for me, hard work at the washing machine, until, I thought my back would break. It was there that I met Joel Scheck, a slender lad who worked one of the wringing machines.

“I quit work there and went to work in a box factory. I spent four years at that, making berry boxes at 6 cents a hundred.

“What chance did I have? I had no education, I had been reared as a gypsy and at the time when every young girl is budding into womanhood and having a good time with her friends in little entertainments I was compelled to kick away at a box making machine.

“I married Joel Scheck when I was 17 years of age. He was only a boy and we went to live on San Julian street.

“At that time I went to work at my mother’s lodging house. I did the work for her for a while, and would then hurry home and do the work at my own home.

“I had never had the fun that other girls have, of going to theaters, and entertainments, so that what wonder was it that I should be lonesome when my husband left me in the evening? He rarely ever spent an evening with me.

“He went out early and came in late, and I was there all by myself, fearfully lonesome, while he was out enjoying himself.

“Then came the voice of the tempter.

“It was at my mother’s house that I met Ernest Stackpole. He was a boarder there, and in that way we met every day. He said he was just in from Arizona, and he always had plenty of money.”

(At this point, I should state what Aurellia did not then know: that the dashing young Stackpole was actually a convicted burglar and armed-robber, who had just fled Utah after a successful heist.)

“At first he would tease me when I went to his room to make up the bed and sweep. Then he wanted me to drink, and he showed me what nice drinks he could make. I paid little attention to him until he became so persistent that in a moment of weakness I accepted a small glass of wine from him.

“That was the beginning of the end. After that he was always importuning me to drink. When my husband was around we all three drank, and so I didn’t think it was so bad after that.

“Then we gradually became more intimate. We went to downtown cafes at all hours of the night, my husband being always along. We went to theaters and entertainments, to beaches and parks, and Stackpole was always putting up the money.

“My husband drank the liquor and accepted the hospitality and never paid a cent. I was only a girl and knew nothing of the ways of a girl’s ruination. At the cafes I saw other young girls drinking. Many of them became drunk and had to be carried away.

“Stackpole offered me all the things I had never enjoyed. He spent money lavishly. He took us places, and for the first time In my life. I had a chance to see pretty plays and enjoy the beaches.

“The evenings were awfully lonesome until he came, and then it was my downfall.

“I thought my husband was unkind to me, and the easy, polished ways of Stackpole appealed to me. A woman sometimes forgets the right for the easy downward path.

“It was a sorry day for me that I accepted Stackpole’s invitation to go to an afternoon matinee, for we later went to a cafe. There he made a drink for me, and when I had swallowed the stuff I didn’t know what had happened to me. My mind was a blank. When I came to my senses I was in a room with him.

“Then he had me, and he knew it. When he went away he wrote five times to me before I answered, and then he began to talk of the killing. I did not appreciate what it meant until he had written many times. I dared not tell my husband, for I feared Stackpole. He told me that if I told he would kill us all.

“To protect my husband I dared say nothing. When he returned he told me to come to him or the killing would begin at once.

“What could I do? I went to him and was his slave again. I did as he said. I drank the drugs he gave me and did not know what I was doing. I threatened to tell the police, and he said that if I did it would only precipitate the murder, for he would kill us all. On the night of the killing he told me that he would kill us all if we dared to say anything against him.

“The events of that night seem to be more like a hideous dream, a dream which has been with me constantly until I feel that I will lose my mind. I see it all over again until my eyes start from my head.

“Would l care If they had hanged Stackpole? I would not have anyone hanged, but I have ceased to think of him. I never want to see him again.

“I am homesick, so homesick until I feel that I will go crazy.”

The Herald journalist asked what Aurellia was homesick for – her mother? The lonely surroundings of her previous life?

“Neither,” she answered, her eyes beginning to fill with tears.

Perhaps she was homesick for Joel, the journalist suggested. (“A moment later I realized how heartless the question was”, he admitted.) He saw her reel back as if she had been struck. Then she slumped and held her face in her hands.

“Oh, how I miss him,” she said. “In the daytime I want him until I wish I could die. But at night I lie over there in my cell and look up at the darkness and wonder if he can know how I want him. I see his face and hear his voice calling to me and there I lie until the first gray light of the morning streaks in through the east windows and the birds in the matron’s room welcome the morning.

“Then I feel that I have lost all that is worth while in life and it fairly tears my soul from me.”

The journalist left after asking about what she planned to do when she was released. (Live with her brother in Garvanza. Learn a profession. Make someone happy.) As he stood outside the door, waiting for the matron to open the iron gates, he heard “a low, heartbreaking sob” from inside the room; the last recorded utterance of Aurellia Scheck.

At the time of Aurellia’s release, Ernest Stackpole was just beginning his life sentence in San Quentin. He was violent enough to quickly establish himself as a jailhouse bully, but he occupied this station for only a few months until he received a humiliating beating from a four-foot-high Puerto Rican dwarf who had been imprisoned on a charge of statutory rape.

He was paroled in 1927, after serving 21 years – he was in his 50s, and seemed “quite an old man”, according to the warden. He immediately resumed his career of crime and was captured the following year after being shot in the leg during a hold-up in Sacramento. He spent the rest of his life in jail.

Sources: Los Angeles Herald, Sep 16, 1906 (the main interview and picture of Aurellia). The case was reported on frequently in the same paper from June 15 to August 31, 1906. Los Angeles Herald Sep 28, 1906 (the dwarf story); and the Oakland Tribune, June 17, 1924 and May 14, 1928 (the details of Stackpole’s later life).