The Union Rescue Mission is well-remembered for its historic home at 226 South Main, where it held forth for fifty-plus years. That site, a labyrinthian place made up of two large linked structures, was famously felled for parking in the mid-1990s, though continues on in the memories of many. Before 226, the Mission spent a near quarter-century in another structure: it is long forgotten, as is the streetscape around it, all obliterated in the name of Civic progress.

Truth be told, the Mission had a collection of “first homes.” There was an office at 431-433 South Spring, larger rooms in a converted saloon near Second and Main, and through the 1890s, a nomadic tent life under canvas roofs on lots located at Second and Spring, First and Los Angeles, and/or First and Spring. The Depression of ’93 and the Panic of ’01 certainly helped send men into the tents.

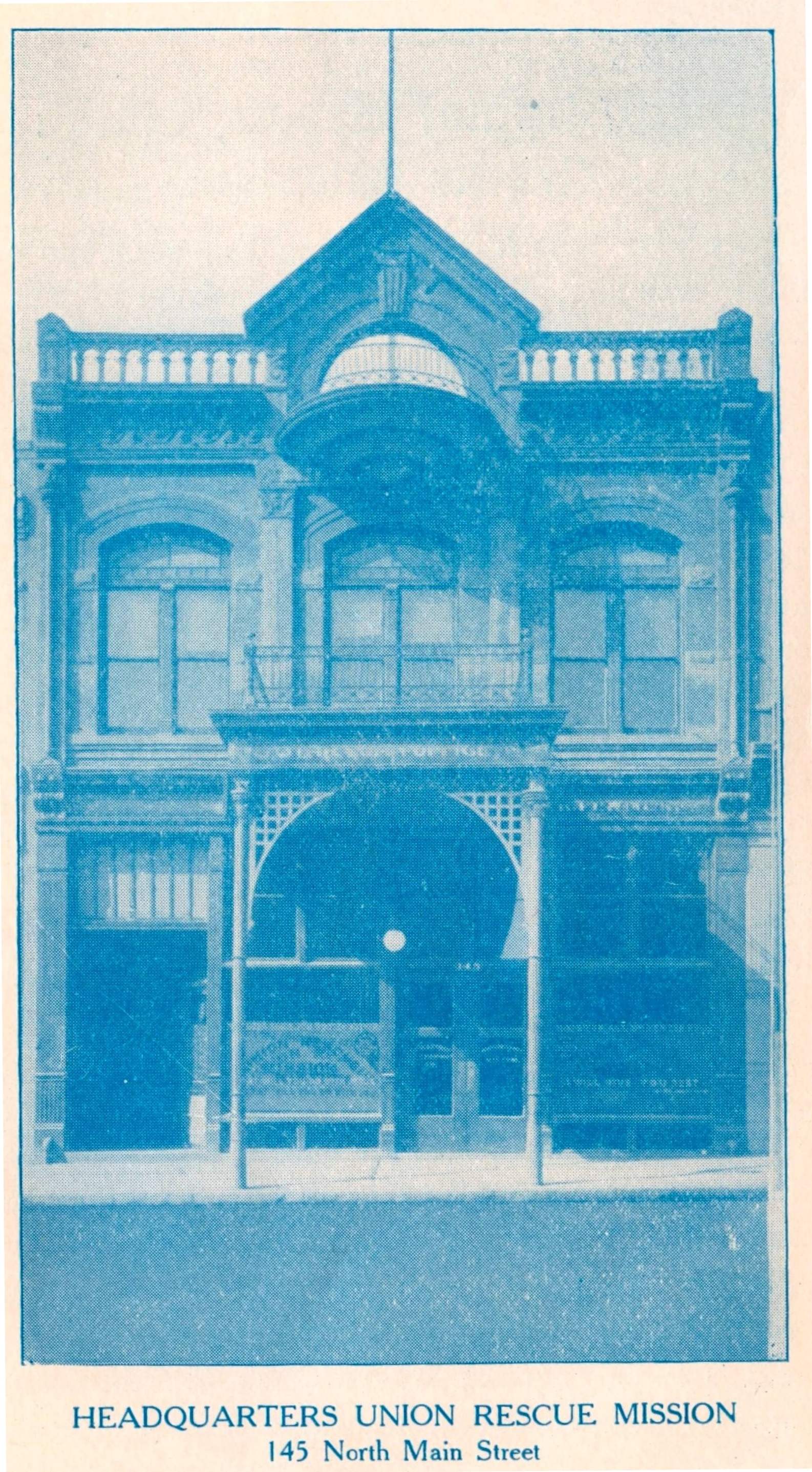

In March of 1903, the Pacific Gospel Mission set down roots in a narrow, two-story structure at 145 North Main. (This is a view of Main in 1891, from out the window of the Natick, looking north across First, our Mission at 145 would be up the block, flush against the left side of image.) After they move into 145, the Pacific Gospel Union AKA Pacific Rescue Mission becomes, under the able hand of Union Oil (besides Lyman Stewart’s tutelage, many early Mission movers and shakers were UO bigwigs, e.g. Giles Kellogg and Robert Watchorn, or Union friendlies like Herbert G. Wylie, et al), the Union Rescue Mission.

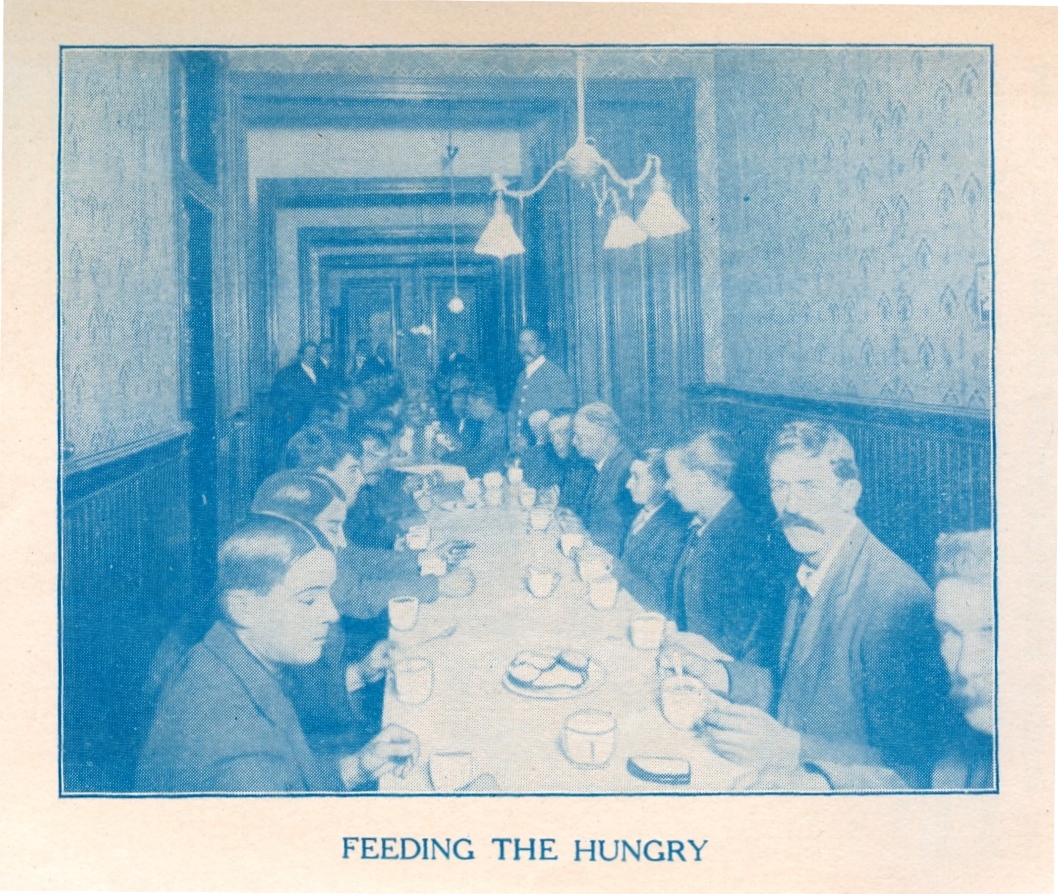

Though 145 was not large, the rented rooms there and its evangelical crew produce great work — in 1906 they held 1,800 services; gave food, clothing and shelter to 2,700; saw 3,201 men and women converted to Christ; and reunited 132 families. The next year Union Rescue buys the building outright. Testimonials from those turned from drink and crime blossom. It is at this time, 1907, that indignant saloon keepers and liquor wholesalers took their protests to the City Council and had the Mission’s colorful public enterprises curtailed.

In 1908 the Mission on Main boasted “one of the cleanest, brightest mission halls to be found anywhere.” From its reading and class rooms, dining and lecture hall, poured a thousand-plus every year, who, lost and helpless, found salvation. At this time Stewart and Thomas Corwin Horton, Bible teacher at the Mission, begin a Bible institute, whose fundamentalist evangelical work stretch world-wide (but that is another story).

The ‘teens and ‘twenties continue without great incident (see men get their 1917 Thanksgiving turkeys here); there are moments of financial hardship, usually relieved at last minute by a healthy pledge. There was even some worry (as it could be called) that they’d done their job too well; they were preaching to good-size congregations of the saved (as was their newly-formed Church of the Open Door), and, in 1920, alcohol was made illegal — certainly THAT was going to quiet things?

Of course, in short order, the Mission realized the need for a relocation: services in helping the needy were growing both in demand and taxed by their quarters at 145. Then, in June 1923, the citizens of Los Angeles authorized $7.5 million in bonds to raze a large parcel of land at Spring, Temple and Main for a City Hall. This sealed the fate of 145. Much of 1924 is spent arguing with the City over value (the URM estimated 48k, the City offered 37: the two parties settled on 43k in 1925).

Thus what was once a rather vibrant block — this being a shot of some of it, from the 1906 Sanborn, showing our Mission at 145 (upper right) surrounded by vaudeville, and liquor wholesalers, and female boarding, that euphamism for one of those less savory occupations — well, just go and compare it to that same square of land from the 1950 map, post-City Hall.

Not that we all don’t have a deserved fetish for our City Hall; but 145 was a charming little building, with its elliptical transoms, spindlework’d porch, with another balcony and railing across an open-pediment roofline (this was lost a bit with the addition of their larger sign) and its slender pilasters leant the whole affair a sense of lightness.

Not to mention the whole rest of the block — here we see it from 115 up to the hotel at 151, the large building across Court St. is the 1896 J. A. Bullard Block. Because there’s what looks to be demo fencing, nor does the Bullard appear to have any windows, I think it’s fair to assume this was during the early moments of her removal. Which means time is limited for everybody.