Should you step into the lobby of the King Edward Hotel at the corner of 5th and Los Angeles Streets in L.A.’s historic Skid Row, and pause to admire the black and gold Egyptian marble fixtures, ionic columns and sweeping mezzanine stair, the odds are better than good that the fellow behind the counter will draw your attention to the clock above the desk and the fancy raised initials just below it.

And in answer to your predictable question, he’ll reply: “Teddy Roosevelt! He stayed here when he visited Los Angeles.”

A Presidential sleepover would be a point of pride for any establishment–all the more so in a young city in the far west. How marvelous a fact, and no wonder the King Eddy’s staff is so quick to share it. (We’ve confirmed that this information has been passed down through oral tradition since at least the mid-1970s.)

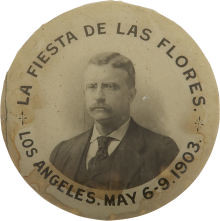

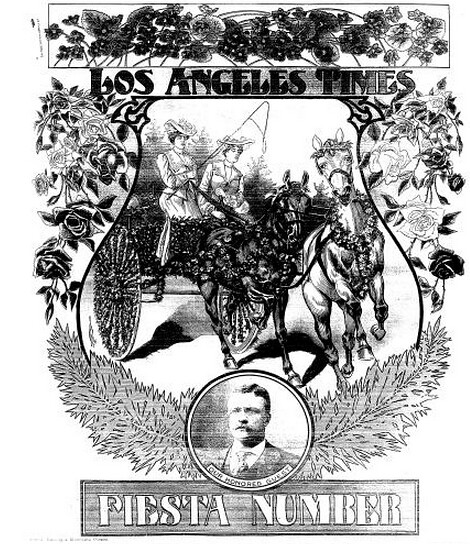

There’s only one problem. Theodore Roosevelt’s famous visit to Los Angeles was on May 8, 1903. He attended the Fiesta de las Flores parade, and stayed that night at the fashionable Westminster Hotel at 4th and Main Streets, two blocks away.

The King Edward didn’t open until 1906.

Oh, but then Roosevelt must have stayed at the King Edward on a later tour of the Southland, right?

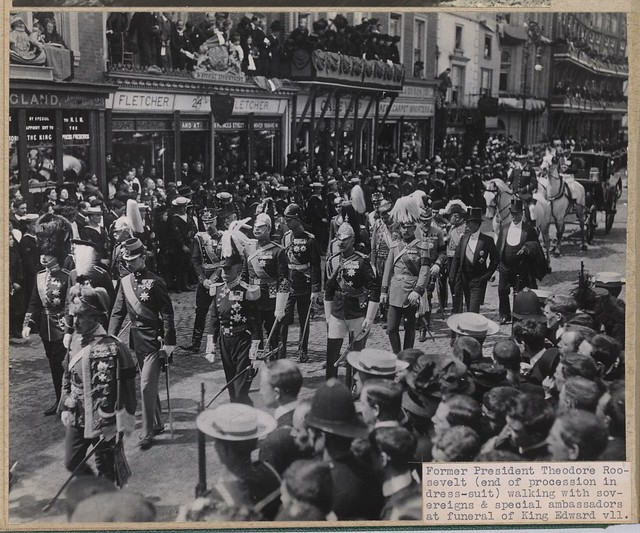

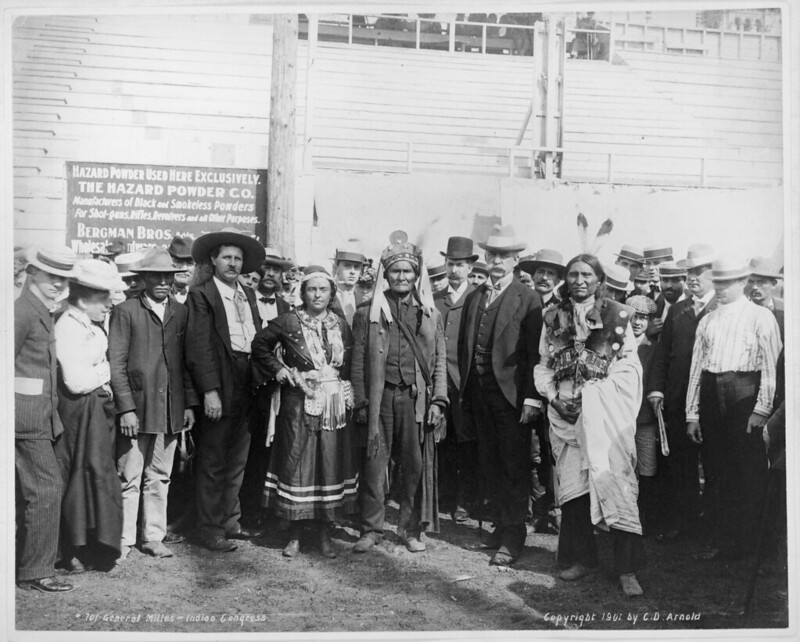

Well, historical records do show that Roosevelt return once more to Los Angeles, for two days in March 1911, when the ex-President spoke at Occidental College and Throop Polytechnic.

His stay at Pasadena’s Hotel Maryland was well publicized, and included a poignant meeting with an aged slave who had been owned by Roosevelt’s maternal family in Antebellum Georgia.

But there appears to be no documentation of a stop at the King Edward or any other Los Angeles hotel.

So why in the name of all that’s historical are the initials T.R. stuck up above the desk of the King Edward Hotel today?

We’ve been wracking our brains, and have come up with a few theories worth floating.

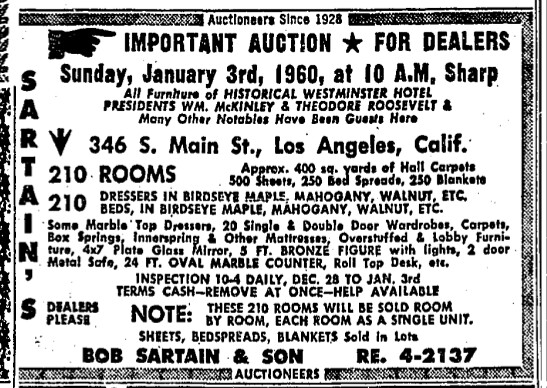

Perhaps before the Westminster Hotel fell to the wrecking ball in 1960, someone went to the auction and bid on a piece of commemorative marble, transporting the legend of a Presidential visit along with the physical artifact back to the nearby establishment?

A tempting notion, but a rare 1920s-era promotional map printed by the King Edward includes a photo of the lobby, which while printed using the halftone technique which makes it impossible to “zoom in” and see finer details, certainly appears to already show a set of initials there beneath the clock.

Well, could they represent an owner of the hotel? The King Edward was built by architect John Parkinson and operated in its early years by Colonel E. Dunham, Tommy Law and Thomas L. Dodge. Not a “T.R.” in the bunch.

Having weighed and sorted these and other, less reasonable, possibilities, we’re prepared to come down on the side of one unsupportable, but eminently pragmatic solution: that the patriotic initials are merely a tip of the hat to a popular politician, and an answer to any testy patron who might question the red-blooded Americanism of a hotel named for a foreign king.

We reckon that’s as good a theory as any, and we’re sticking with it until and unless something better comes along.

Which leaves the initials “T.R.” above the desk of the King Edward, and the abiding oral tradition of the great man’s visit, something of a mystery–but no less beguiling for that. Since everyone who knew the real answer is dead, we’re free to craft our own myths to pass along to Angelenos who’ll come after. Why do you believe the initials “T.R.” are there under the clock in the King Eddy?

This meditation on time and memory was written on the occasion of the upcoming shuttering of the King Edward Saloon and the auction of its equipment and memorabilia.