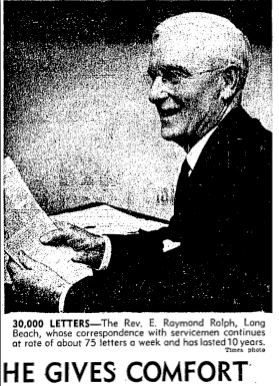

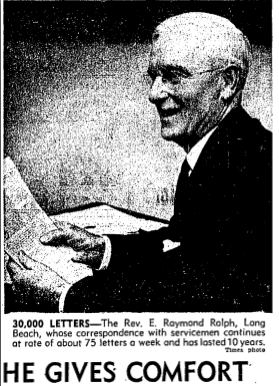

No mother ever wants to open the door to find men waiting to tell her that her child has died. For Mrs. Darius G. Farrar, Sr. of Camden, Arkansas, the news came not long after Darius Jr.’s 18th birthday: he had been killed at Iwo Jima. It was three years later when they brought the body home, and plans were made to bury him at the National Cemetery in Fayetteville, that mama started wishing she had a picture of what her boy looked like when he went off to fight. He’d shipped out from Los Angeles, and had made a visit to crowded downtown Los Angeles where he’d had his portrait taken. But he had been in such a hurry, the studio had to send the prints on to him in Guam. And when a buddy mailed them home after Darius’ death, they were lost in the mail. Mrs. Farrar was resourceful. She wrote to Reverend E. Raymond Rolph of Long Beach and asked his help in finding the negative—from among all the dozens of photo studios in downtown Los Angeles, with their tens of thousands of photos of Marines.  Pastor Rolph, a Baptist, was not chosen randomly. The servicemen of World War II and their families had no greater friend than this energetic soul, who was said to have sent more than 30,000 messages of encouragement or sympathy from 1942-52, officiated at more than a hundred military funerals, attended a thousand marriages (and performed a dozen), talked damaged men out of self-harm or harming others, welcomed a hundred babes named in his honor and somehow kept his thousands of pen pals straight through a convoluted filing system of his own devising. So when Mrs. Farrar asked for that figurative needle in SRO Land’s hay — “I have written to everyone I could think of. God knows how I have just wanted one good picture of Darius” — Pastor Rolph was not discouraged. He enlisted the aid of the Los Angeles Times, which gave the request a couple of column inches on page 11 of the April 2 edition, between stories warning of the dangers of socialized medicine and the tragedy of twin boys born by Caesarian to a dead mother in Illinois. And the photographic studio workers of Main and Broadway saw the story, and they went to their files. But not everyone has a filing system as precise, as well-kept, as Pastor Rolph. It was Winifred Thompson, manager of the Austin Studios at 707 South Broadway, who found the negative, in a brown envelope, in a box of trash. The kid was smiling fit to beat the band. She had prints struck, sent them on to Pastor Rolph, and he sealed them up with yet another letter to one more grieving mother. It was waiting for her when she came home from the burial. “From the depths of a true mother’s heart I want to thank you,” she wrote.

Pastor Rolph, a Baptist, was not chosen randomly. The servicemen of World War II and their families had no greater friend than this energetic soul, who was said to have sent more than 30,000 messages of encouragement or sympathy from 1942-52, officiated at more than a hundred military funerals, attended a thousand marriages (and performed a dozen), talked damaged men out of self-harm or harming others, welcomed a hundred babes named in his honor and somehow kept his thousands of pen pals straight through a convoluted filing system of his own devising. So when Mrs. Farrar asked for that figurative needle in SRO Land’s hay — “I have written to everyone I could think of. God knows how I have just wanted one good picture of Darius” — Pastor Rolph was not discouraged. He enlisted the aid of the Los Angeles Times, which gave the request a couple of column inches on page 11 of the April 2 edition, between stories warning of the dangers of socialized medicine and the tragedy of twin boys born by Caesarian to a dead mother in Illinois. And the photographic studio workers of Main and Broadway saw the story, and they went to their files. But not everyone has a filing system as precise, as well-kept, as Pastor Rolph. It was Winifred Thompson, manager of the Austin Studios at 707 South Broadway, who found the negative, in a brown envelope, in a box of trash. The kid was smiling fit to beat the band. She had prints struck, sent them on to Pastor Rolph, and he sealed them up with yet another letter to one more grieving mother. It was waiting for her when she came home from the burial. “From the depths of a true mother’s heart I want to thank you,” she wrote.