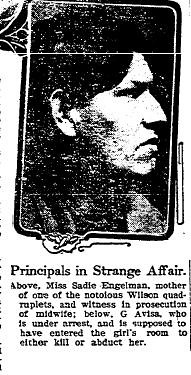

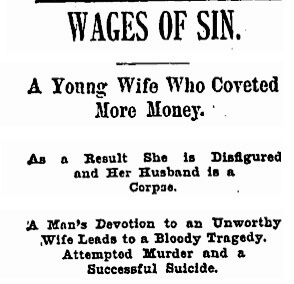

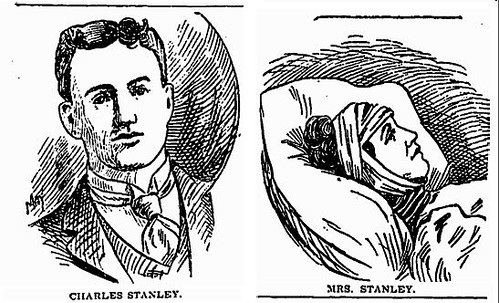

A girl of 16, Sadie Engelmann, left her family to try her hand at fame and fortune on the stage. In San Diego, her beauty, if not her craft, won her many admirers, among them a dashing stenographer with the US Navy by the name of John Harvey.

When Sadie found herself abandoned by John and in need of a midwife, she checked in to the Bellevue Avenue Lying-in Institute in Los Angeles, where she deposited a newborn boy, whom she left in the care of the proprietress, “Dr.” Catherine Smith. At this point a disagreement ensued between Sadie and “Dr.” Smith concerning the details of the babe’s status. Sadie claimed she left the child temporarily in “Dr.” Smith’s care, in order to earn enough money to pay the bill she incurred during her delivery. She testified that once she had settled her debt she would re-assume custody of the child. “Dr.” Smith alleged Sadie sold her the newborn outright to pay off her debts and to free herself from the undue burden of its care. Whatever the exact nature of their understanding, “Dr.” Smith appears to have taken possession of the child, and in turn sold the baby boy to a Mrs. W.W. Wilson, who had already acquired three other infants in a nefarious plot to appear as if she were the mother of quadruplets.

The miraculously sudden appearance of the quartet of babies attracted the attention of the authorities, who promptly summoned Mrs. Wilson, “Dr.” Smith, Sadie Engelmann, and other parents of the illegitimate infants in to court to sort out the affair. During the course of the trial, Sadie Engelmann claimed to have been accosted and threatened by various burglars “of Mexican aspect,” who, she alleged, were sent by “Dr.” Smith to dissuade her from testifying.

According to court testimony, Mrs. Wilson grew despondent after many years of trying to bear her own children, and eventually conceived the plan to to fill her and her husband’s home with a readymade brood of abandoned youngsters. She enacted this plan years before the quadruplets affair, procuring three children, whom she presented to her husband as his own, each time using an ingenious series of pads and pillows to trick him into believing she had indeed carried each child to term. The children were in the couple’s possession at the time of Mrs. Wilson’s attempted quadruplets heist.

The trial ended with the conviction of “Dr.” Smith on the charge of child stealing. Upon appeal, the court handed down a sentence of 5 years probation, during which Smith was to cease and desist the practice of midwifery.

Eventually, Mrs. Wilson was permitted to adopt the three children in her care before the trial, and to become a foster-mother to the two girls among the quadruplets. The boys, including Sadie Engelmann’s son, did not survive infancy. Mrs. Wilson went on to take on more foster-children, and to run a daycare facility in Hollywood.

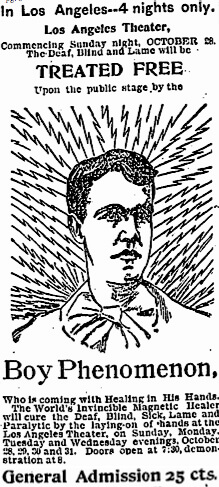

This battle of titans began in the fall of 1894, when the miraculous magnetic healer known as the Boy Phenomenon (aka Dr. Stuart Franklin Temple) came to the city “with Healing in his Hands,” offering his free curative powers to the deaf, blind, sick lame, paralytic and whomever else who managed to drag themselves to the Los Angeles Theater. Before the healing commenced, Temple’s manager, the Great Diagnostician Professor W. Fletcher Hall, lectured on the medical research supporting the application of Vital Force and Animal Magnetism. The duo took the show on the road to Pasadena, San Bernardino and San Diego, but then parted ways in 1895. The following year, Professor Hall reappeared in Los Angeles with a new protégé, a young German boy he discovered among the “rubbers” in the Turkish baths at St. Louis, who must have impressed Hall with his restorative manual dexterity. His given name was Carl Herrmann, but Hall dubbed him The Boy Wizard, and distinguished him in advertisements from Dr. Temple by claiming he “daily generates ten times more magnetism that the former Phenomenon.”

This battle of titans began in the fall of 1894, when the miraculous magnetic healer known as the Boy Phenomenon (aka Dr. Stuart Franklin Temple) came to the city “with Healing in his Hands,” offering his free curative powers to the deaf, blind, sick lame, paralytic and whomever else who managed to drag themselves to the Los Angeles Theater. Before the healing commenced, Temple’s manager, the Great Diagnostician Professor W. Fletcher Hall, lectured on the medical research supporting the application of Vital Force and Animal Magnetism. The duo took the show on the road to Pasadena, San Bernardino and San Diego, but then parted ways in 1895. The following year, Professor Hall reappeared in Los Angeles with a new protégé, a young German boy he discovered among the “rubbers” in the Turkish baths at St. Louis, who must have impressed Hall with his restorative manual dexterity. His given name was Carl Herrmann, but Hall dubbed him The Boy Wizard, and distinguished him in advertisements from Dr. Temple by claiming he “daily generates ten times more magnetism that the former Phenomenon.”