I’ve seen the needle and the damage done

A little part of it in everyone

But every junkie’s like a settin’ sun.” — Neil Young

Morphine may have been legal in 1910, but it wasn’t being distributed for free. If you were an addict, you’d still have had to find the money to pay for your drug of choice. Faced with the difficulty of obtaining the necessary funds, one creative Angelino devised an unusual plan.

The unidentified hophead spun an imaginative tale to the managers of several local plumbing establishments. He told the gullible men that he was representing a medical institute, explaining that it was headed by a New York physician who was planning to occupy an entire floor of the Alexandria Hotel!

The unidentified hophead spun an imaginative tale to the managers of several local plumbing establishments. He told the gullible men that he was representing a medical institute, explaining that it was headed by a New York physician who was planning to occupy an entire floor of the Alexandria Hotel!

According to the man, the doctor hadn’t yet spoken with the management of the Alexandria; however, he had been engaged to find a plumbing company that could handle the installation of several very large and extremely heavy bathtubs.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the “glib tongued drugster” then produced plans which called for the placement of the tubs, which were eight feet long, six feet wide, made of lead-lined iron, and described as “big enough to hold a dray horse”.

Blinded by visions of a job worth at least one thousand dollars ($24,049.74 current USD) and some priceless publicity, the plumbers didn’t look too closely at the man who was pitching such a sweet deal. And they also never questioned the absurdity of operating a medical institute in the Alexandria Hotel! If they’d paid attention, they’d have seen what Mr. J.A. Hooser (of Hooser & Buchanan, 1302 South Main Street) ultimately observed.

Mr. Hooser admitted that he’d initially believed the man’s story. He told a reporter that “I fell for the song. He was a clean-cut fellow enough, and fairly well dressed, as far as I saw…but when he was on his way out, I noticed that the coat tails he wore were a bit frayed and that his shoes were laced with twine.” Mr. Hooser went on to say: “Right there I did not think much of the job and scolded myself for wasting time with a crank. But the next day I found out that this same fellow borrowed a two dollar tape from the shop after showing my tinner his arm full of hypodermic needle marks to prove that his New York doctor had cured him.”

Apparently the man had run the same scam all over town, “borrowing” tape from Hooser’s shop, tools from another – all of which he then sold for drug money.

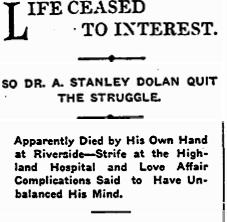

Maybe the anonymous drugster should have used his ill-gotten gains and visited one of the many doctors in SRO Land who claimed to treat addiction. But then, the treatment that they used may have done more harm than good.At that time one of the most aggressively marketed treatments for morphine addiction was heroin!

Maybe the anonymous drugster should have used his ill-gotten gains and visited one of the many doctors in SRO Land who claimed to treat addiction. But then, the treatment that they used may have done more harm than good.At that time one of the most aggressively marketed treatments for morphine addiction was heroin!

Ironically, heroin (a derivative of morphine first successfully synthesized in 1897 by the Bayer Company) was thought to be a non-addictive substitute for morphine. Bayer’s intentions may have been good; but we all know what the road to hell is paved with.

Can a company seek redemption? If so, maybe Bayer has already been forgiven. Around the same time that they launched heroin, Bayer introduced another drug that would have an enormous impact on the world – aspirin.