The desperate man walked into the Bank of America branch and crossed the lobby to the second teller window–to Mrs. Joy Holker, 28, the one with the kind eyes. He handed her a brown envelope and a note which read “This is a holdup. Fill up the envelope. Also have a jar of acid.” She obeyed, quickly stacking $540 in $10 bills and passing them across the counter. But as she counted, she gave her robber the once-over. She didn’t buy it, not from this guy. As he turned away, she came out from behind the counter and chased him onto Broadway, screaming “Stop that man!”

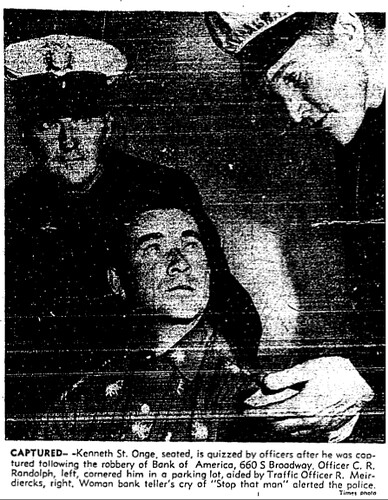

A motorcycle cop, Charles Randolph, heard her cries, as did patrolman R. Mierdiercks. They took off after the robber, who had darted east on 7th Street. He turned south down Spring, and tried to hide in a parking lot mid-block. They busted him there, and he surrendered peacefully.

Kenneth St. Onge, 35, had a cap pistol, a bottle of colored water and a sob story. He said he’d come out from Detroit with his wife and seven sons last September, but couldn’t find any work. For three weeks, the family slept in their 1947 Studebaker, until wife Esther found work as a waitress. They’d then moved into a quonset hut at 1480 Landa Street, rent $25 a week plus utilities. After two months, the electric bill came. It was $67, which is how they learned their landlord had wired up an apartment, a trailer and a garage to their meter. With only one pair of decent shoes for all the children, he’d spend his days driving first one, then another child to attend a class or two, then pick up Esther. Whatever she made in tips, that was their dinner fund. Everything else went to the landlord.

Then Esther got pregnant again, and couldn’t stay on her feet all day. They had nothing left. He didn’t know what else to do, so he did this. “I guess I knew I’d get caught, but I figured at least the State would have to take care of my wife and kids,” he mused.

Los Angeles briefly fell in love with the sad sack, especially after he appeared on local television bemoaning his fate. Over $1000 in donations poured in, along with clothes for the kids and a job for daddy at City of Hope. The family was offered a furnished home in La Puente for nothing down.

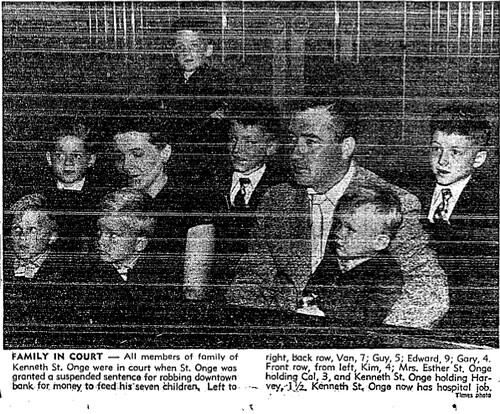

Just over a month after his life of crime fizzled out, a proud Kenneth St. Onge celebrated Easter with his wife and children in court, as Judge Thurmond Clarke ruled “Because of your record, your family and your children, I am going to grant you probabtion in this case. For robbing a national bank, I’ve certainly been very lenient.”

“People have been so kind. I know everything is going to turn out all right now. This is,” said St. Onge, “the best break I ever had.”

And all he had to do to get it was to cross over to the dark side. There’s a lesson in there somewhere, we guess, maybe nothing more profound than that most folks like to hear about someone who’s got it even worse than they do.

Photos: Bank of America from LAPL, others Los Angeles Times