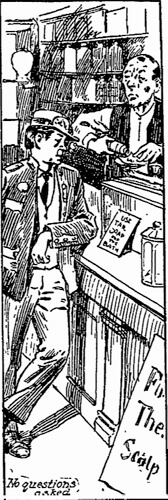

Up until the fall of 1906, an Angeleno could walk into a pharmacy downtown (or discreetly dispatch a messenger boy) without a doctor’s prescription and buy morphine, cocaine, opium, codeine, heroin, laudanum, carbolic acid or other potentially fatal poisons, packed for his or her convenience in nickel, dime, or 25 cent bags.

Image Credit: LA Times Historical Archive

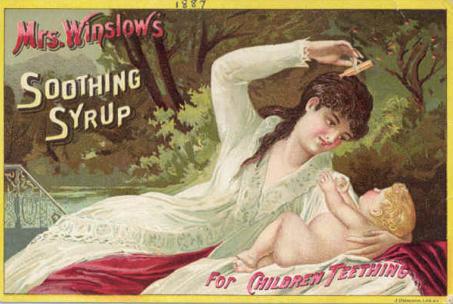

Of course, many of these drugs were highly touted miracle ingredients in the elixirs of the day, thought to be so beneficial, in small doses, that they were suitable for children.

Image Credit: Addiction Science Network

But 1906 brought a slew of new ‘poison control’ laws, which required pharmacies to employ only registered pharmacists to dispense drugs, to maintain a “poison registry” of the names and addresses of customers who purchased medications deemed dangerous, and to refrain from dispensing such drugs without a prescription from a licensed physician. The laws were not strictly enforced until May of 1907, when a crusading Secretary of the State Board of Pharmacy by the name of Charles B. Whilden made a sweep through 33 drug stores in downtown Los Angeles and bought dope at 16 of them.

At Wilson’s Pharmacy at 6th and Figueroa a young boy behind the counter sold Whilden carbolic acid; a few days later a young lady, presumably the boy’s mother, but no registered pharmacist, sold him laudanum. Similar transactions occurred at Frank T. Rimpau at 355 North Main Street, F.J. Giese at 108 North Main Street, Los Angeles Pharmacy at 212 West Fourth Street, Angelus Pharmacy at 801 West Third Street, and many other downtown retailers. The pharmacies were fined $100 for each violation. Several of the owners argued at sentencing that if future regulations prohibited them from selling opiates they would have to close their doors, as these products accounted for more than half their total profits.

In June Whilden continued his poison investigation in Chinatown, where he arrested four proprietors of opium dens, even though the dens were licensed and the opium sellers paid a monthly fee of $25 to the city.

All offenders were released after payment of fines, and business returned to usual in the downtown dens of vice.