Los Angeles in the 1890s was a city rife with vice. For every respectable young woman safe in her father’s mansion on Bunker Hill, there were uncounted hussies parked in the cribs of old Chinatown, providing comfort, company and contagion for a price.

It was no surprise that fraternizing with loose women could result in a venereal disease. Sporting men had paid the drippy price for centuries. Various preventatives and cures of dubious efficacy circulated by word of mouth, and in the coded advertisements that financed Colonel Otis’ empire. Afflicted, a man would submit to cures that could be worse than the disease, suspending disbelief as genial quacks dispensed toxic mercury, arsenic and irritating salves. A man could make a good living catering to the anxieties of men who visited prostitutes. Some of them weren’t even sick, though ironically, these fantasists were among the most difficult to cure.

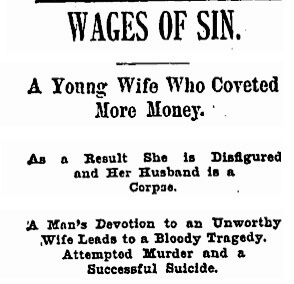

It was October 5, 1889 when the eager ears of L.A.’s gossips cocked to take in information about a troubled pair, the unfortunate Mrs. Dr. Plato Marcus White and her errant mate, a doctor specializing in victims of love. The lady arrived from San Francisco after receiving a letter from her husband, who had she groused used her money to take offices at 31 North Main Street in March, and who had only allowed his wife brief visits in Los Angeles since. He always was “in quite a stew to get rid of her” and she came to believe he had another woman, if not women, in his life.

Whatever the circumstances of their estrangement, Dr. White sent the lady a letter saying he would not live with her again, and she fairly flew down the coast to confront him. She arrived on Saturday night, and not finding Plato in his office, went straight to the police and demanded they send out search parties. She was humored; Plato stayed lost. The lady then searched his office, and found two mash notes shoved under the door from one Minnie Westfield, of the Bumiller block on North Spring Street, site of a rooming house frequented by many noisy young ladies. Off went Mrs. White on a strumpet hunt, but she was directed to the wrong room, and retired to the doctor’s office to wait him out.

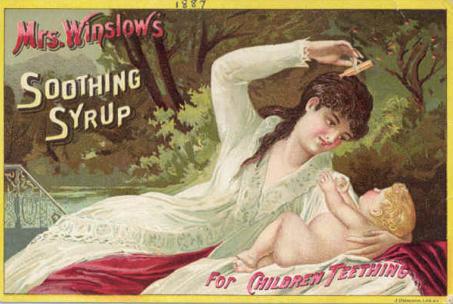

The good doctor was a valuable member of early Los Angeles society, offering as he did discrete and purportedly effective treatment against the many unfortunate after effects of youthful and aged debauchery. And further, he promised that his nostrums were less toxic than those of his peers. There would be no mercury, sandalwood oil or spicy cubebs for Dr. White’s patients.

In January 1890, operating out of rooms at No. 6 San Pedro Street (parlors 1 and 2), Dr. White placed the most explicit ad of his career, as an experiment which he did not repeat. For young men, he promised treatment for such “youthful follies… as Mental Debility, Depression of Spirits, Gloominess, Love of Solitude, Despondency, Timidity, Seminal Weakness in all its stages, Pimples on the face, Noises in the Head, Dimness of Vision, Palpitation of the Heart, Wakefulness, Weakness of the Back, Premature Decline, and many diseases which lead to insanity and death.” For the middle aged “who are afflicted with Syphilis – in all its horrible forms – a disease which, if neglected or improperly treated, curses the present and future generations—Ulcers. Sore Throat. Bone Pains. Specific Blood and Skin Troubles. Gonorrhoea, Gleet and Stricture; or who suffer from Nervous Debility, Exhausting Drains upon the Fountains of Life, Excesses, Premature Loss of Manhood, Impotency, or any private disease of Sexual or Urinary Organs should secure Dr. White’s services… an early call or a friendly letter may save future suffering and shame and add golden years to life.”

Ordinarily, such blatant language was not necessary. Men knew how to read the classified section, and well understood what was being offered when the headline read “Disorders of Men” and the small print promised “no mercury.”

Could Dr. White really offer a cure? The first true anti-syphilitic agent, Salvarsan, was not discovered until 1908. But centuries of experimentation had produced numerous substances that could alleviate symptoms and soothe worry. We don’t know if Dr. White was a quack or true healer. It may be enough that he provided that most effective nostrom: peace of mind.

But whatever the quality of his care, later in October the Times published further information on his marital maladies. Mrs. White was still camped out in the doctor’s Main Street office, but the “frisky” doc continued to elude her. But she could be appeased somewhat to know that he was thinking of her, having communicated with the San Francisco Examiner, which too had been reporting on his conjugal woes. For that paper, he delineated the circumstances of their San Bernardino courtship, when he had married the lady to keep her from making good on a suicide threat. He took issue with the Examiner’s apparent description of Her Vexedness as “a charming graduate of an eastern medical college” when she was rather a practitioner of “magnet healing” and further, a decrepit 45 years old.

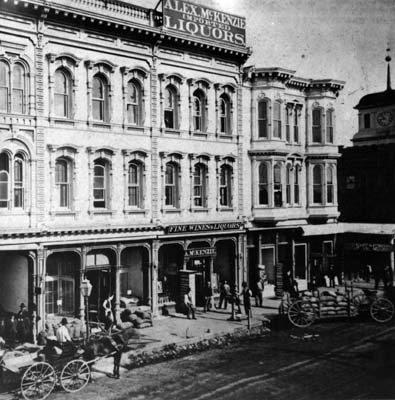

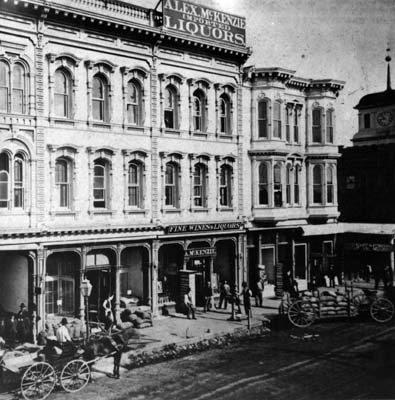

As for the wife, she believed the material in the San Francisco paper was meant to trick her into rushing back to look for the doctor in that city, but she would not be fooled. She already knew that his mail went to a lawyer in the Phillips Block (above), and that a Spanish woman who wore goggles visited that office daily. She believed this mysterious figure was picking up the doctor’s mail, and after having her followed, knew this woman then took Temple Street to Beaudry and went south.

The doctor’s wife had many thoughts about the women in his life. Of Minnie Westfield, author of the semi-literate love notes, she mused “he’s dodging her, too. He must have not less than three women on the string here. The one who signs herself Westfield is named Minnie or Mary Green, and she used to be employed as a servant at the Winona, a boarding-house on Temple Street. I have seen here at the Doctor’s office, and I saw her passing up and down the street today looking up at the window, then she came and peeped into the hall and went away. There is another woman—a little woman—who came here the other day and inquired for the Doctor, and gave such a lame excuse, together with a fictitious address, that I am confident she is one of Dr. White’s victims also. I tell you, Dr. White is no gentleman!” If he would only come to her and be honest about his heart, she would give him up in a second. But, she warned, “if the Doctor don’t come to me and act like a man, I will follow him to the end of the earth.”

On October 26, 1889, the Times reported that Dr. White had come out of hiding and agreed to speak with his wife. Afterwards, he became convinced she was going to kill him, and asked police for protection. He then spent the night of October 24 in Evergreen Cemetery, sitting on his first wife’s grave and fingering a pistol, but he decided not to kill himself. Instead, he went back to his living wife, and announced that the two of them would be “at home” should any daring or morbidly curious friends wish to pay a visit.

In December 1889, the Whites’ marital miasma again reached public ears when Mrs. White, confined to a bed in her husband’s new offices at number 6 San Pedro Street, sent word to police that she had been deserted, was destitute and needed help. Soon a reporter from the Times was on hand to take down all the dirt.

Mrs. White told a tale of brutality, fraud and neglect. Her immediate problems began, she wheezed, when she drank a dram of wine from the decanter on Plato’s dresser, wine that he made no move to share. Immediately after, she was taken sick, her husband left, and now she believed she might starve because her throat was so sore. Sore throat or no, she rambled on about her husband’s medical expertise, in magnetic healing. Why, did you know the whole thing was a fraud? And that Plato loved another woman and had probably poisoned his spouse so he would be free to stray? Her plan, if he did not return with some money, was to formally charge him with desertion and see him behind bars.

In January 1890, Dr. White appeared in a police station seeking a chaperone for a meeting with his surly misses, but was informed that cops weren’t available to baby sit. And then, silence. We can only assume the Whites worked out their differences, for Mrs. White was unlikely to keep quiet otherwise.

Then someone, perhaps a disgruntled patient, must have reported Dr. White’s activities to the Health Department, for in July 1893 he was called to answer to their Board on discrepancies between the State certificate he had shown when registering in the city, and the type of medicine he was practicing. The only result of the hearing was that the State Board was to be notified about him. Later, reporters cleared from the room and the doctor’s wife was quizzed about her qualifications as a midwife, then allowed to leave.

Dr. White, sensing things were getting a little hot in the old pueblo, took a trip to Hawaii, returning in September to provide an interview about his adventures. The resulting puff piece, coming on the heels of so much prurient reporting, says much about the journalistic ethics of the early Los Angeles Times, and quite a bit about our friend White.

He was described, vaguely if not entirely inaccurately, as a “noted specialist of this city.” His report included a call for the United States to annex the islands (which he said most intelligent Hawaiian also desired), a claim that he had been welcomed by the medical professionals and received with honors by the Board of Health and quarantine station, his opinion that leprosy was incurable, and a litany of his purported credentials: graduation from the Medical College of Ohio (Cincinnati) and certificates from Indiana, New York and California.

Further, “he is the oldest and most firmly established specialist in Southern California, if not, indeed, the state. Dr. White treats exclusively nervous, special and chronic diseases. He has splendidly furnished and equipped office at No. 128 North Main Street, in the New McDonald Block. These offices contain all modern improvements and conveniences for the use of his patients, including electric lights, etc. He also possesses a splendid medical laboratory and many rare anatomical specimens… Dr. White’s patients are generally of the better class of citizens. His business is conducted in an open and above-board manner, and is, therefore, in striking contrast to that charlatan and carpet-bag lot of quacks who often make their advent into the community only to fleece and entrap the unwary. No sooner have they made their ‘stake,’ than they are found moving on to other places where their reputations are unknown.” We also learn that he does a booming trade practicing medicine by mail.

By February 1900, fourteen years after he hung out his L.A. shingle, Dr. White was advertising his practice as being exclusively for the benefit of male patients–and can you blame him? He also claimed to have no partners, and to no longer be found at No. 128 North Main, suggesting that perhaps his wife or some other person had usurped that august practice. Dr. White was now easily found at No. 114.

Perhaps his wife had revived the work with which she supported herself in San Francisco. White quickly moved back into the old offices, and changed his ads to read DR. WHITE & CO., but the writing was on the wall: his life was still chaotic.

As for the marriage? It limped along until April 1902, when Mrs. White (whose name we learn, only at this late date, was Florence L.), filed for a divorce from Plato. It was granted in May, and in November he filed for bankruptcy (with debts of $2051.60 and assets of $850.75), in part because he could or would not pay her $4 weekly support. Among his other debtors: most of the city’s newspapers, in whose classified columns he sought his patients. For nearly three years we hear no more of from Dr. White, who, however hard it was to live with her, seems to have owed his success to the aid of his helpmeet Florence.

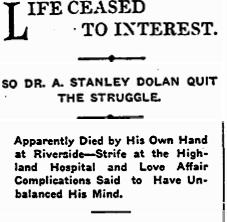

And then, after dozens of ads touting his medical services, this final notice was placed in the Times on December 10, 1904:

Dr. White’s sad end was reported in the Southern California Practitioner:

He was soon forgotten, and other doctors took his place. We will see more of them In SRO Land, but a tender spot shall remain in our most tender places for our friend, weird Dr. White.

Image credits: ads and headlines from the historic Los Angeles Times via ProQuest, McDonald Block litho and Philips Block photograph from the USC Collection, McDonald Block photograph from the LAPL Collection.