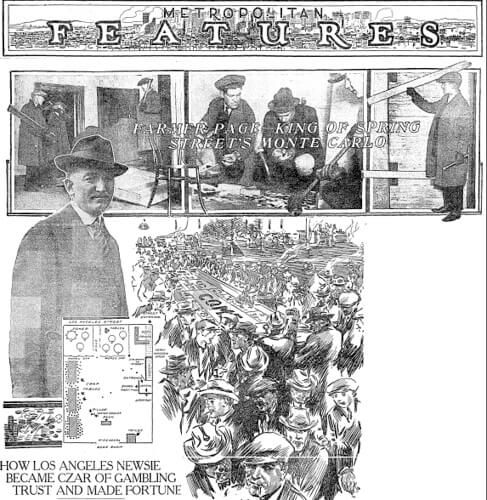

Image courtesy of the LA Times Historical Archive

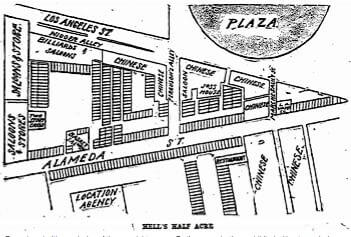

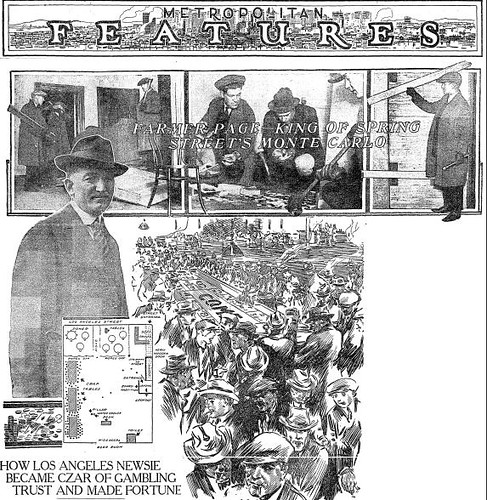

By the time he was 12, Milton B. Page had his own corner of downtown Los Angeles, as well as his nickname “Farmer,” for his shambling gait and ill-fitting clothes. By morning, Farmer Page sold newspapers at 2nd and Spring; by night he rolled dice and played poker with his fellow newsboys in the alley nearby. After a stint playing valet to his younger brother Stanley, a famous jockey, Farmer returned to the city and eventually conducted a big game in the basement of the Del Monte Bar on West Third Street. Club after club followed, until Farmer owned controlling interests in five establishments, and was the de facto leading gambler in Southern California.

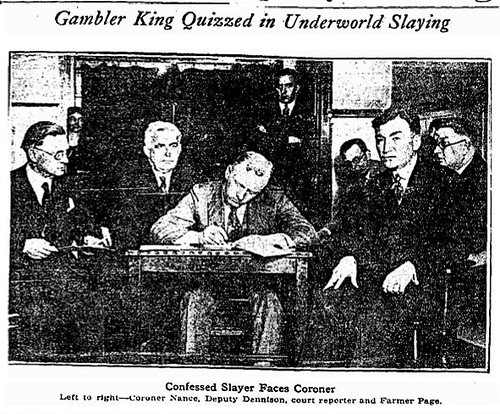

While Page and his dealings were well known to the downtown police force, his first significant clash with the law didn’t come until 1925, after he bested a disgruntled former employee, Al Joseph, in a gunfight at the Sorrento, on 1348 West 6th Street. Page claimed the shooting was in self-defense, the culmination of a drawn-out underworld feud between himself and Joseph, who had become a member of the notorious “Spud” Murphy gang of San Francisco, and had made repeated threats on Page’s life. Page turned himself into the authorities after the slaying.

In the court proceedings, Joseph was portrayed by the defense as a vicious and turbulent man, a hijacker and a thug, who “packed a business gun of large caliber, and a smaller social gun for festive occasions.” Farmer was found innocent of murder, and was excused his 50 thousand dollar bond.

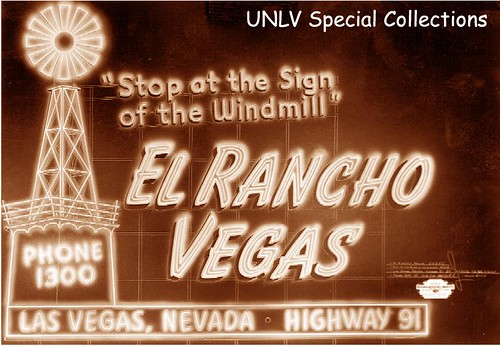

The trial might have freed Farmer, but the testimony of his many associates revealed the extent of the gambler’s bootlegging operations, and resulted in eventually driving Farmer out of downtown and on to a gambling boat moored off the coast of Santa Monica. From there he followed fellow kingpins Guy McAfee and Tudor Scherer to Las Vegas. These big shots of the Roaring Twenties banded together and bought controlling stakes in such hotels and casinos as the El Rancho Vegas. Fittingly, “Farmer” Page died in a hotel at 2205 West Sixth Street in 1960, at the age of 73. He was survived by a son, the seemingly mild-mannered bookstore owner, Milton B, Page, Jr.