Although Japanese, and as such always an outsider to the Anglo culture of SRO land, G. Kurokaua was a respected longtime employee of the Ramona Saloon at 307 South Spring Street. But for all his years in the bar, he failed to tune his ear to the friendly jibes and japes that were the habit of the place. Already crabby with an undiagnosed stomach ailment that pained him, the gentleman took grave offense when a patron, perhaps aware of Kurokaua’s remarkable thrift, joked that he had doubled his salary by raiding the till. Mortified, Kurokaua went to his employer, who laughed the remark off as the joke it was. But Kurokaua brooded. If his customers believed he was dishonorable, what was the point in living? His Japanese friends tried to appease him, it was just a case of an American being American, nothing worth taking to heart. It was no use. Several days after the slight, Kurokaua went to his rooms at 215 Boyd Street, readied his tanto knife with cloth around the outer side, plunged the blade into his belly and managed a cut of nearly a foot in length before losing consciousness. He then fell back upon his bed to die, a traditional Samurai honor suicide, harakiri, in downtown Los Angeles.

The Abduction of Baby Toto

“Toto”, the two-year-old daughter of Mary Smith, a single mother who had a room in the home of the Harver family at 634 Gallardo street, went missing one spring day in 1906. Mary’s neighbors, who rushed to the house to comfort her, soon confirmed that each had seen the same distinctive beggar woman drifting down the street earlier — a “strange creature” who “several times … remarked that she had no means of earning a livelihood.”

From the women’s description, the police identified the beggar as Lizzie McGuire, who was well known to them, and not only because she had survived being shot some years ago by her boyfriend, Paddy Walsh, who was now serving a sentence in San Quentin. They suspected that she had taken the little girl either to hold her for a reward or to carry along with her on one of her periodical begging tours of the country. The latter possibility was bolstered when they discovered that Lizzie had fled her quarters in a rooming house on East Second street the day before.

While police departments across southern California were contacted with details of the case and photographs and descriptions were sent out of Toto and Lizzie, a detective called Roberds doggedly searched second-class lodging houses downtown, following a sighting of the woman on the corner of Fifth and San Pedro.

Five days after the abduction, during which time Lizzie had dragged the child around various run-down establishments in an attempt to evade capture, Detective Roberds tracked her down in a dingy room in 644 San Julian street.

Lizzie, who “sullenly refused to say anything to detectives when her lair was discovered”, was arrested. However, as the police had known all along, she would never be prosecuted. She had survived her boyfriend’s attempt to kill her all those years ago, but she hadn’t exactly come through unscathed — the shot that he’d fired had hit her in the head, leaving her not only with a bullet scar on her forehead that made her detection by the police far easier than it would otherwise have been, but also with a brain that didn’t quite work as well as it used to. The prosecution was over before it began: Lizzie was deranged, and therefore mentally unfit to stand trial.

And Toto? She was returned to her tearful mother, apparently physically unharmed, although she appeared wan and was “sadly in need of a bath”.

Sources: Los Angeles Herald, April 20 and 21, 1906.

Crib District Gets a Makeover

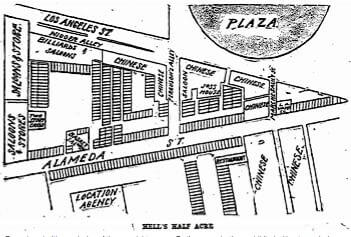

They weren’t pretty but they sure were cheap, and easy to find. All an Angeleno had to do to ease his itch before the turn of the century in LA (or maybe pick up another one) was head downtown to Alameda and Ferguson Alley to an area known as the Cribs. There, in the tenderloin, you’d find a rookery of one-story shacks divided into even smaller compartments, called cribs, which were rented to “fallen women” of all nationalities for $1.50 to $3.00 a night.

At least that was the case until February 1st, 1902, when the Cribs underwent a sudden transformation. At dawn carpenters and sign painters invaded the district, and by the end of the day the Cribs were reinvented as “cigar stores” and “dressmakers,” where the likes of “Frankie” and “Louise” and “Georgie” would sell “Gents Neckwear” and do “Corset Stitching,” “Feather Curling,” and “Fancy Work.”

The ploy, designed to skirt the most recent in a series of crackdowns on vice in the crib quarter, didn’t hold up for long. On February 5th, police raided Cribtown and arrested 17 women for vagrancy. The patrol car only had room for 13 prisoners, so the remaining four were led on foot to the police station, followed by a crowd of saloon bums and macquereaux (pimps, or macks).

Chaos ensued in the station, where the booking desk sergeant struggled to record the incomprehensible names of the French and Belgian prisoners. The majority of the women were released on bail before nightfall, put up by the main landlords of the cribs, who shelled out nearly 4 thousand dollars for their return. A few months after this bust, the crib district finally went dark when the police, clergy, the Salvation Army, and women crusaders allied to shut down the saloons that anchored the neighborhood.

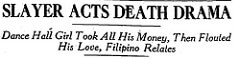

Dance Hall Siren

In ancient times, the Greeks wrote of three beautiful Sirens – women who were part bird and part woman, and who lived only to seduce sailors with their haunting songs.Sailors who charted a course near islands inhabited by the Sirens were inevitably shipwrecked, their vessels smashed to bits on nearby rocky shores.

In modern times, Sirens were more likely to inhabit a bar stool than an island. The unlucky sailor who fell for a modern Siren may not have been literally dashed to bits, but he would suffer a similar symbolic fate – a broken heart.

Dominga Villa, a young sailor from the Philippines, first laid eyes on Emma Hanmore in a Main Street dance hall. Emma danced her way into Dominga’s affections, and then slipped a greedy hand into his wallet. The lovesick sailor lavished the dancer with gifts and cash until he was tapped out.“She broke me,” he said. “I love her. I give my life for her but she just fool me and then say bah, she not want me.”

After turning up unannounced at Emma’s apartment with the last of his cash, Dominga was crushed when he saw another man’s clothes draped over a chair. He demanded an explanation, apparently not realizing that what he’d bought and paid for was Emma’s time and the pretense of a relationship, not her love. Perhaps her secret heart wasn’t for sale, or maybe the man’s clothing in her apartment belonged to another in a long line of suckers.

Emma was able to divert Dominga’s attention from the mystery man’s clothes in her apartment by agreeing to meet him at the dance hall that evening.They later returned to Dominga’s hotel room, where Emma told him that she was finished with him.

Dominga was shattered — his love had been abused. Even worse, the woman didn’t show any remorse for having played him. In fact, she sardonically sang him a love song, and laughing, prepared to walk out of his life. Dominga later recalled “I went mad”, pulling out a pistol and gunning Emma down.He then turned the weapon on himself but was only injured, and lived to tell his story in court.

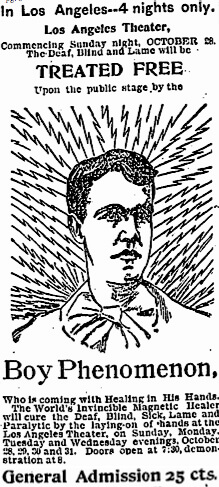

Boy Phenomenon vs Boy Wizard

This battle of titans began in the fall of 1894, when the miraculous magnetic healer known as the Boy Phenomenon (aka Dr. Stuart Franklin Temple) came to the city “with Healing in his Hands,” offering his free curative powers to the deaf, blind, sick lame, paralytic and whomever else who managed to drag themselves to the Los Angeles Theater. Before the healing commenced, Temple’s manager, the Great Diagnostician Professor W. Fletcher Hall, lectured on the medical research supporting the application of Vital Force and Animal Magnetism. The duo took the show on the road to Pasadena, San Bernardino and San Diego, but then parted ways in 1895. The following year, Professor Hall reappeared in Los Angeles with a new protégé, a young German boy he discovered among the “rubbers” in the Turkish baths at St. Louis, who must have impressed Hall with his restorative manual dexterity. His given name was Carl Herrmann, but Hall dubbed him The Boy Wizard, and distinguished him in advertisements from Dr. Temple by claiming he “daily generates ten times more magnetism that the former Phenomenon.”

This battle of titans began in the fall of 1894, when the miraculous magnetic healer known as the Boy Phenomenon (aka Dr. Stuart Franklin Temple) came to the city “with Healing in his Hands,” offering his free curative powers to the deaf, blind, sick lame, paralytic and whomever else who managed to drag themselves to the Los Angeles Theater. Before the healing commenced, Temple’s manager, the Great Diagnostician Professor W. Fletcher Hall, lectured on the medical research supporting the application of Vital Force and Animal Magnetism. The duo took the show on the road to Pasadena, San Bernardino and San Diego, but then parted ways in 1895. The following year, Professor Hall reappeared in Los Angeles with a new protégé, a young German boy he discovered among the “rubbers” in the Turkish baths at St. Louis, who must have impressed Hall with his restorative manual dexterity. His given name was Carl Herrmann, but Hall dubbed him The Boy Wizard, and distinguished him in advertisements from Dr. Temple by claiming he “daily generates ten times more magnetism that the former Phenomenon.”

The Boy Wizard began his run in January of 1896 at the Music Hall, and also offered private consultations at $1.00 a pop at the Pacific Coast Magnetic Institute, his and Hall’s establishment on Third and Broadway. Unlike the Phenomenon, the Boy Wizard allegedly possessed a deft touch with the ladies. According to his manager the Boy Wizard had an “unbroken record in treating complaints peculiar to the gentler sex and his Magnetic Force has proved a boon to the suffering woman.”

If only I had a dime …

It didn’t take long for the erstwhile Phenomenon, Dr. Temple, to discover that the Wizard’s ads featured the same testimonials as his so recently had, and Temple promptly brought suit against the magnetic newcomer. The lawsuit occasioned some lovely copy in the LA Times, including this lede: “Dissension reigns in the realms of occultism, and there is the grind of clashing auras and the shock of opposing batteries.”

All parties appear to have settled out of court, as the papers contain no mention of a trial date or ruling, and The Boy Wizard’s trail goes cold a few weeks after the lawsuit was threatened.

manager of Kohler the Oriental Seer, and in new digs, at the California

College of Occult Sciences at 245 South Spring. But the partnership

turns out to be a short-lived affair. Before three months have passed

the institution and Dr. Temple have vanished.

The Drinks Are On Me!

Andrew McLemore was feeling generous as he entered the Waldorf Bar at 527 S. Main Street. His pockets were stuffed with $896 in cash. That kind of coin can burn a hole in a man’s pocket, so Andrew ponied up enough bread to buy drinks for himself, and for everyone else in the house!

The affable benefactor would likely have continued his largess, if he hadn’t been interrupted by the cops. It seems that he hadn’t actually earned the money – in fact he’d just robbed Lloyd’s Bank, one block over at 548 S. Spring St. One of the tellers had trailed Andrew to the bar, and then flagged down a passing police car.

Andrew may have been acting on a generous impulse when he bought drinks for Waldorf’s barflies, but the law was unimpressed. He was handcuffed and hauled off to the slammer.

Note to Andrew: No good deed goes unpunished.

Jake Will Cure Your Ache

Convinced she had poisoned her sister and that the girl would surely die, Mrs. Austin telephoned for a doctor. Somehow the police were notified of a suicide at the address, and came to investigate. They found the crampy sister none the worse for wear for her dosing—which was a lucky break, since Arnica is rarely taken internally, and can cause illness or death–and Mrs. Austin most abashed.

(L.A. Times, May 28, 1896)

Jamaica Ginger has a long and fascinating history, in SRO Land and throughout America. A favorite remedy for pretty much anything that ailed you, this rocket-powered ginger jolt was packed to bursting with health-giving alcohol–around 150 proof. All was well until the 18th Amendment was passed, and anti-drink regulators began requiring the addition of adulterants that made Jamaica Ginger, commonly and most affectionately called “jake,” taste horrible.

Many formulas were introduced in an attempt to produce a palatable, legal Jamaica Ginger recipe, among them Harry Gross’ and Max Reisman’s 1930 version, packed with delicious tri-ortho cresyl phosphate (TOCP), a plasticizer. Shortly after the new formula debuted, tens of thousands of jake drinkers began presenting at hospitals complaining of mysteriously drooping toes and other symptoms of paralysis. Upstanding citizens who had hitherto kept their benders on the down low were exposed by the easily recognized Jake-Leg Shuffle, a limp shared by many habitués of the concoction.

The poisonous formulation was soon discovered and taken off the shelves, but the damage had been done. While some jake abusers recovered, others suffered long term nerve damage.

For more on jake leg’s cruelties, and the syndrome’s role in the history of the Delta blues, see Dan Baum’s 2003 New Yorker feature (PDF download).

As for us, we’re sticking with Vernors!

Pass Me a Napkin, or I’ll Shoot!

Ex-convict Ray Davis, 31, was seated at the counter of a café at 456 South Main Street, when he realized that the napkins were just out of reach. He asked the man next to him, Bob Sahagain, a 21 year old Sioux, to please pass him a napkin. Bob chuckled, saying “I can’t”, then turned away from Ray to continue his conversation with a friend.

Ex-convict Ray Davis, 31, was seated at the counter of a café at 456 South Main Street, when he realized that the napkins were just out of reach. He asked the man next to him, Bob Sahagain, a 21 year old Sioux, to please pass him a napkin. Bob chuckled, saying “I can’t”, then turned away from Ray to continue his conversation with a friend.

Ray thought that Bob was being rude and asked him once again to hand over a napkin. Bob turned to him, laughed, and repeated that he couldn’t do it. Maybe it was a case of diner rage, or perhaps Ray was flashing back to his prison days, taking his meals in a crowded mess hall, where manners were an artifact of a society too far removed. Whether they were past, or present, the demons in Ray’s head prompted him to pull out a .25 caliber pistol and shoot the young man in the back.

What Ray had failed to notice about Bob was that he was totally blind – he had two glass eyes! The patrons of the café decided that if anyone needed to be taught a lesson about etiquette, it was Ray. Surely shooting someone at the dining counter of an SRO Land café could be considered the height of bad manners. A small mob formed immediately following the gun play. Ray was soon disarmed and the patrons began to beat him, breaking his jaw. They continued to beat him until the cops arrived and ended the confrontation.

Bob was reported to be in fair condition at General Hospital.Ray was booked at Central Jail on suspicion of assault with a deadly weapon with intent to commit murder.

I think I’ll have dinner at home tonight.

The Case of the Medical Electrician aka Abortionist

“

“

“The girl was thirsty and wanted ice water constantly. She wouldn’t eat much, and vomited black stuff. She was in a great deal of pain on her left side and her abdomen.” So ended the short life of Lillie Hattery, age 22, on February 5th, 1897, in the clinic of “Dr.” Calvin S. Hastings, Medical Electrician, according to testimony presented at his murder trial.

When Lillie Hattery came from San Bernardino to visit her sister in Los Angeles in late January, she arrived with the names of people rumored to perform “criminal operations.” “Dr.” Hastings, who practiced without the benefit of a medical license, was third on the list. According to testimony at the trial, Lillie paid $200 for Hastings’ services, which included multiple applications of electrical current to the back and abdomen, as well as a surgical procedure, which resulted in copious blood loss by the patient. Lillie suffered from fever, convulsions, and severe pain for a week, during which Hastings treated her solely with electrical stimulation. Two licensed medical doctors examined Lillie’s body after it had been delivered to the morgue, and determined that the cause of death was septicemia due to blood poisoning. They also determined that she had been pregnant and undergone an attempted abortion.

At his trial, Hastings testified that Lillie Hattery suffered from an injured ankle, which he treated with electrical stimulation. He claimed that she appeared in good health until the very last moment before she succumbed to what he assumed must have been an internal abnormality such as a diseased heart or some other affliction. Although the prosecution presented evidence of perjury and intimidation of witnesses on the part of both Hastings and his nurse, along with surgical instruments found in Hastings’ offices that were commonly used for abortion procedures, as well as closed court testimony from a young woman who had recently undergone the criminal operation in Hastings’ care and had almost died, the jury still found Hastings innocent in the death of Lillie Hattery.

Hastings was even able to post bond during the trial, thanks to the generosity of a female admirer, and re-located his Medical Electrician clinic for business down the street in the Hammond Block at 120 1/2 South Spring. Hastings’ Medical Electrician Clinic’s Grand Opening so provoked a dentist in residence there that the man came to blows with the rental agent, and promptly moved out of the disgraced office building, where, he claimed, no decent woman would now darken a door.

Spring Street, looking south from First Street 1900-1910

USC Digital Archive

After his acquittal, Hastings married the woman who posted his bond. In later years she turns up as one of the many sufferers who find miraculous relief at the hands of the great healer, Rama, of the Rama Institute at 305 ½ South Spring Streets, Los Angeles. One can only wonder why Mrs. Hastings’ own husband was unable to heal her deafness with his electrical stimulation.

LA Times Historical Archives

Dr. Calvin S. Hastings was still practicing medicine without a license in 1911 when the state attorney filed a complaint against him during a campaign to shut down so-called “Quack Chink Doctors.”

Tarzan’s Dad at the Hickman Trial

In an era where a celebrity journalist like Dominick Dunne (1925-2009 R.I.P.) covered the sordid murder trials of O.J. Simpson, Robert Blake and Phil Spector it should be noted that this is not a new phenomenon.

Hickman Court Hearing: William Edward Hickman sans necktie at his court hearing. Immediately to Hickman’s right is longtime Sheriff Eugene W. Biscailuz and to his immediate left is his lead defense attorney for the trial Jerome Walsh.

Case in point- was the 1928 trial of William Edward Hickman for kidnapping, murder and dismemberment of Marion Parker. For two tension packed weeks the trial created such a sensation of tabloid headlines that even Charlie Chaplin came to the Hall of Justice to get an up close and personal look at Hickman. Famed journalist and screenwriter Adela Rogers St. Johns attended and reported on the trial just as she had done during the prosecution of Loeb and Leopold and later Bruno Hauptmann for the Lindberg kidnapping.

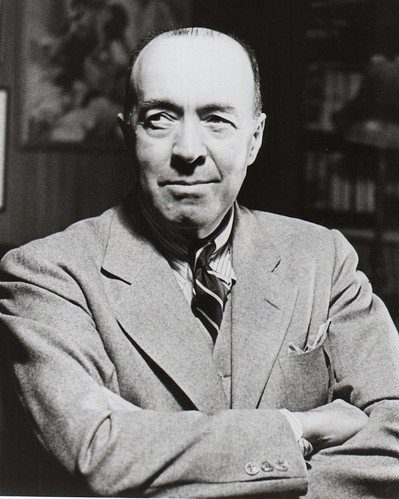

Edgar Rice Burroughs famed fantasy author best known as the creator of Tarzan of the Apes covered the duration of the trial in 13 columns for the Los Angeles Examiner. The articles can be found at https://www.erbzine.com/mag17/1768.html

It is particularly interesting to see how Burroughs in this series of OP-ED pieces thinly disguised as columns gave it his best effort to seal Hickman’s fate. Hickman’s guilt was never in doubt but his counsel presented one of the earliest attempts at the insanity defense. Not only did Burroughs not buy into Hickman’s defense attorney’s contention that their client was insane, Burroughs protested that he didn’t see any need for a trial at all. And Burroughs sarcasm was evident when he mocked the defense’s dermatography demonstration by trying it at home with his own son. In the test actually performed at the trial, Hickman removed his shirt and his skin was scratched with a metal object. According to the defense in explaining the significance of dermatography, a bright colored long lasting mark was supposed to prove mental instability.

Edgar Rice Burroughs in 1934

On the other hand Burroughs nicely encapsulated a couple of the trial’s most dramatic and emotionally wrenching moments. When the autopsy photos of Marion Parker’s nude dismembered body were passed to the jury, the woman in the third seat was so overwhelmed by the first of these black and white 8X10s that she fainted on the spot. And the most dramatic moment in the trial was the appearance and testimony of the prosecution’s last witness, Marion’s father Perry Parker. In the winter darkness of December 19, 1928 Parker delivered the ransom to Hickman on South Manhattan Place. When Hickman opened the car door, Marion tumbled out just as Hickman sped off. Parker ran up to find an unspeakable horror. Lying in the gutter was the lifeless body of his daughter still wearing her little gingham dress. Rouge had ghoulishly been painted on her cheeks. Her limbs were missing and her eyelids had been sewn open. It was a crime that continues to shock for its brutality over eighty years later. Hickman’s insanity defense was rejected by the jury and he was executed by hanging at San Quentin on October 19, 1928. Hickman got weak in the knees as he began to climb the steps of the platform and had to be carried the rest of the way to the top. But that was just a prelude for the real drama. Hickman’s head hit the opening of the chute when he dropped, breaking his fall rather than his neck. It took William Edward Hickman over 15 minutes to die that day by suffocation. Observers reported that the drawn out death scene was so disturbing to watch there were shrieks from the audience and numerous people fainted, including Dick Lucas one of the key detectives who had been involved in the investigation.

Personal Sidebar about Burroughs.

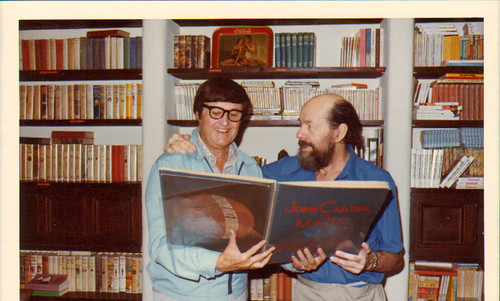

Bob Clampett and John Coleman Burroughs: Clampett and Burroughs reminisce while holding original John Carter of Mars material. This photo is from the early 1970’s.

My dad was only a couple of years older than Marion Parker. About the time of the murder he attended the original Otis Art Institute downtown which he would travel to by streetcar. Another student driven by chauffeur in a limosene became one of my dad’s lifelong friends. It was John Coleman Burroughs, second son to Edgar Rice Burroughs. My dad, already a big fan of Burroughs’ books, visited the Burroughs home frequently and soon got to know the elder Burroughs. Several years later when my dad was an animator at Warner Bros. studio he partnered with Edgar Rice Burroughs and son John Coleman to bring Burroughs’ vision of his Mars series to the silver screen via animation. They worked nights and weekends for over a year and completed quite a bit of development artwork, script treatment pages and a one minute sales reel showing what a John Carter of Mars animated feature might look like. At that time MGM couldn’t see past the success of the live action Tarzan films they were producing. To finance an animated feature was not a proposition that appealed to them at all. Here’s a youtube link to the reel with an audio track of my dad narrating.

This piece originally appeared on the DVD, Beany and Cecil The Special Edition Volume One released in 2000. There have been many other unsuccessful efforts over the years to bring Burroughs’ Mars stories to the screen. However Pixar/Disney is now at work on John Carter of Mars, their first film that will include live action characters blended with CG animation.

Other notable Otis alumni from the 1920s included the two very talented brothers Bob McKimson (creator of Foghorn Leghorn) and designer and layout artist Tom McKimson. Both brothers later worked with my dad at Warner Bros. Cartoon studio. There was also George Maitland Stanley (designer of the Oscar statue, the Astronomer’s monument at the Griffith Observatory, and the fountain at the Hollywood Bowl), John Hench (Key Disney artist for over 65 years and Tyrus Wong (another Disney artist who worked on Bambi) and is now 99 years old. (Otis later became Otis College of Art and Design.)

My dad stayed in close contact with the Burroughs family throughout his life. Danton Burroughs, John Coleman’s son and keeper of the Burroughs legacy, passed away last year.

Thanks to Bill Hillman of Erbzine.

Thanks to Sarah Russin, Director of Alumni Relations at Otis College of Art and Design.

Thanks also to The Watson Family Archive and to Delmar Watson (1926-2008 ) who was like a second father to me.